Panther Media Global/Alamy

Mathematics is a “science which requires a great amount of imagination”, said the 19th-century Russian maths professor Sofya Kovalevskaya – a pioneering figure for women’s equality in this subject.

We all have an imagination, so I believe everyone has the ability to enjoy mathematics. It’s not just arithmetic but a magical mixture of logic, reasoning, pattern spotting and creative thinking.

Of course, more and more research also shows the benefits of doing puzzles like these for brain health and development. Canadian psychologist Donald Hebb’s theory of learning has come to be known as “when neurons fire together, they wire together” (which, by the way, is one of the guiding principles behind training large neural networks in AI). New pathways start to form which can build and maintain strong cognitive function.

What’s more, doing maths is often a collaborative endeavour – and can be a great source of fun and fulfilment when people work together on problems. Which brings me to these festive-themed puzzles, which can be tackled by the whole family. No formal training in maths is required, and no complicated formulas are needed to solve them.

I hope they bring you some moments of mindful relaxation this holiday season. You can read the answers (and my explanations for them) here.

Festive maths puzzlers

nestdesigns/Shutterstock

Puzzle 1: You are given nine gold coins that look identical. You are told that one of them is fake, and that this coin weighs less than the real ones. You are also given a set of old-fashioned balance scales that weigh groups of objects and show which group is heavier.

Question: What is the smallest number of weighings you need to carry out to determine which is the fake coin?

Puzzle 2: You’ve been transported back in time to help cook Christmas dinner. Your job is to bake the Christmas pie, but there aren’t even any clocks in the kitchen, let alone mobile phones. All you’ve got is two egg-timers: one that times exactly four minutes, and one that times exactly seven minutes. The scary chef tells you to put the pie in the oven for exactly ten minutes and no longer.

Question: How can you time ten minutes exactly, and avoid getting told off by the chef?

Dasha Efremova/Shutterstock

Puzzle 3: Having successfully cooked the Christmas pie, you are now entrusted with allocating the mulled wine – which is currently in two ten-litre barrels. The chef hands you one five-litre bottle and one four-litre bottle, both of which are empty. He orders you to fill the bottles with exactly three litres of wine each, without wasting a drop.

Question: How can you do this?

Puzzle 4: For the sake of this quiz, imagine there are not 12 but 100 days of Christmas. On the n-th day of Christmas, you receive £n as a gift, from £1 on the first day to £100 on the final day. In other words, far too many gifts for you to be able to count all the money!

Question: Can you calculate the total amount of money you have been given without laboriously adding all 100 numbers together?

(Note: a variation of this question was once posed to the German mathematician and astronomer Carl Friedrich Gauss in the 18th century.)

Puzzle 5: Here’s a Christmassy sequence of numbers. The first six in the sequence are: 9, 11, 10, 12, 9, 5 … (Note: the fifth number is 11 in some versions of this puzzle.)

Question: What is the next number in this sequence?

Garashchuk/Shutterstock

Puzzle 6: Take a look at the following list of statements:

Exactly one statement in this list of statements is false.

Exactly two statements in this list are false.

Exactly three statements in this list are false.

… and so on until:

Exactly 99 statements in this list are false.

Exactly 100 statements in this list are false.

Question: Which of these 100 statements is the only true one?

Puzzle 7: You are in a room with two other people, Arthur and Bob, who both have impeccable logic. Each of you is wearing a Christmas hat which is either red or green. Nobody can see their own hat but you can all see the other two.

You can also see that both Arthur’s and Bob’s hats are red. Now you are all told that at least one of the hats is red. Arthur says: “I do not know what colour my hat is.” Then Bob says: “I do not know what colour my hat is.”

Question: Can you deduce what colour your Christmas hat is?

Puzzle 8: There are three boxes under your Christmas tree. One contains two small presents, one contains two pieces of coal, and one contains a small present and a piece of coal. Each box has a label on it that shows what’s inside – but the labels have got mixed up, so every box currently has the wrong label on it. You are now told that you can open one box.

Question: Which box should you open, in order to then be able to switch the labels so that every label correctly shows the contents of its box?

Puzzle 9: Just before Christmas dinner, naughty Jack comes into the kitchen where there is one-litre bottle of orange juice and a one-litre bottle of apple juice. He decides to put a tablespoon of orange juice into the bottle of apple juice, then stirs it around so it’s evenly mixed.

But naughty Jill has seen what he did. Now she comes in, and takes a tablespoon of liquid from the bottle of apple juice and puts it into the bottle of orange juice.

Question: Is there now more orange juice in the bottle of apple juice, or more apple juice in the bottle of orange juice?

joto/Shutterstock

Puzzle 10: In Santa’s home town, all banknotes carry pictures of either Santa or Mrs Claus on one side, and pictures of either a present or a reindeer on the other. A young elf places four notes on a table showing the following pictures:

Santa | Mrs Claus | Present | Reindeer

Now an older, wiser elf tells him: “If Santa is on one side of the note, a present must be on the other.”

Question: Which notes must the young elf must turn over to confirm what the older elf says is true?

Bonus puzzle

If you need a festive tiebreaker, here’s a question that requires a little bit of algebra (and the formula “speed = distance/time”). It’s tempting to say this question can’t be solved because the distance is not known – but the magic of algebra should give you the answer.

Santa travels on his sleigh from Greenland to the North Pole at a speed of 30 miles per hour, and immediately returns from the North Pole to Greenland at a speed of 40 miles per hour

Tiebreaker: What is the average speed of Santa’s entire journey?

(Note: a non-Christmassy version of this question was posed by the American physicist Julius Sumner-Miller.)

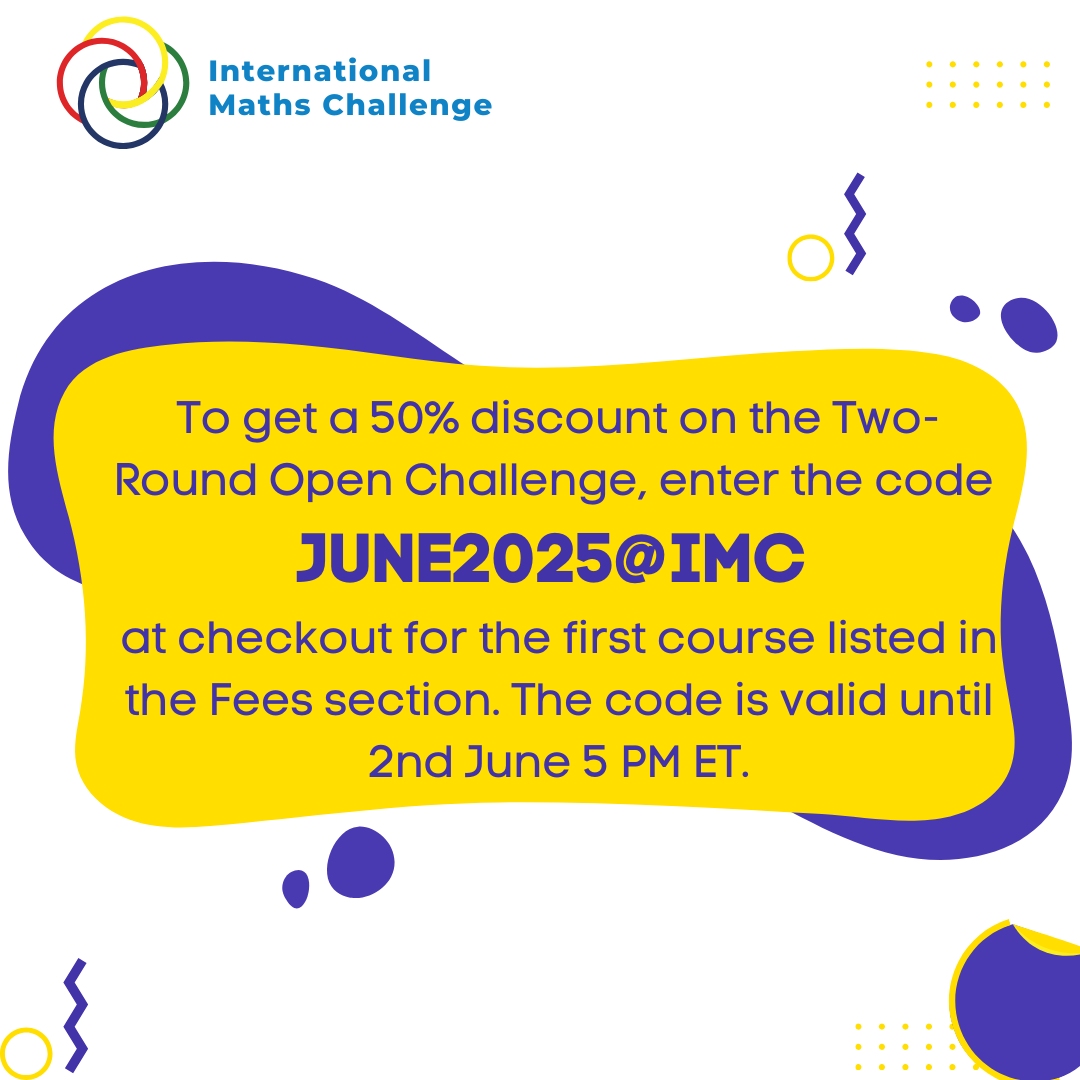

For more such insights, log into www.international-maths-challenge.com.

*Credit for article given to Neil Saunders*