Could a system of eight-dimensional numbers help physicists find a single mathematical framework that describes the entire universe?

Words can be slippery. That is perhaps even more true in physics than it is in the rest of life. Think of a “particle”, for instance, and we might conjure an image of a tiny sphere. In truth, “particle” is just a poetic term for something far removed from our everyday experience – which is why our best descriptions of reality make use of the cold precision of mathematics.

But just as there are many human languages, so there is more than one type of number system. Most of us deal with only the familiar number line that begins 1, 2, 3. But other, more exotic systems are available. Recently, physicists have been asking a profound question: what if we are trying to describe reality with the wrong type of numbers?

Each mathematical system has its own special disposition, just like languages. Love poems sound better in French. German has that knack of expressing sophisticated concepts – like schadenfreude – in a few syllables. Now, in the wake of a fresh breakthrough revealing tantalising connections between models of how matter works at different energy scales, it seems increasingly likely that an exotic set of numbers known as the octonions might have what it takes to capture the truth about reality.

Mathematicians are excited because they reckon that by translating our theories of reality into the language of the octonions, it could tidy up some of the deepest problems in physics and clear a path to a “grand unified theory” that can describe the universe in one statement. “This feels like a very promising direction,” says Latham Boyle at the Perimeter Institute in Waterloo, Canada. “I find it irresistible to think about.”

Many physicists dream of finding a grand unified theory, a single mathematical framework that tells us where the forces of nature come from and how they act on matter. Critically, such a theory would also capture how and why these properties changed over the life of the universe, as we know they have.

So far, the closest we have come is the standard model of particle physics, which details the universe’s fundamental particles and forces: electrons, quarks, photons and the rest. The trouble is, the standard model has its shortcomings. To make it work, we must feed in around 20 measured numbers, such as the masses of particles. We don’t know why these numbers are what they are. Worse, the standard model has little to say about space-time, the canvas in which particles live. We seem to live in a four-dimensional space-time, but the standard model doesn’t specify that this must be so. “Why not, say, seven-dimensional space-time?” Boyle wonders.

Real and imaginary numbers

Many think the solution to these woes will come when experiments uncover a missing piece of the standard model. But after years of effort, this hasn’t happened, and some are wondering if the problem is the maths itself.

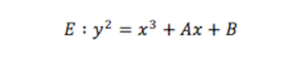

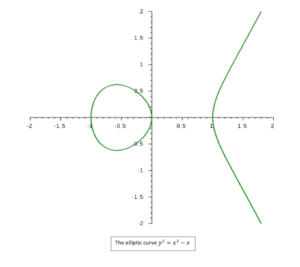

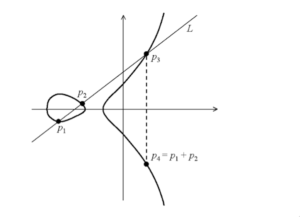

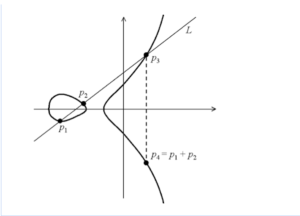

Mathematicians have known for centuries that there are numbers other than the ones we can count on our fingers. Take the square root of -1, known as i. There is no meaningful answer to this expression, as both 1 × 1 and -1 × -1 are equal to 1, so i is an “imaginary number”. They found that by combining i with real numbers – which include all the numbers you could place on a number line, including negative numbers and decimals – they could fashion a new system called the complex numbers.

Think of complex numbers as being two-dimensional; the two parts of each number can record unrelated properties of the same object. This turns out to be extremely handy. All our electronic infrastructure relies on complex numbers. And quantum theory, our hugely successful description of the small-scale world, doesn’t work without them.

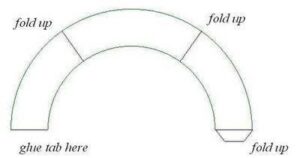

In 1843, Irish mathematician William Rowan Hamilton took things a step further. Supplementing the real and the imaginary numbers with two more sets of imaginary numbers called j and k, he gave us the quaternions, a set of four-dimensional numbers. Within a few months, Hamilton’s friend John Graves had found another system with eight dimensions called the octonions.

Real numbers, complex numbers, quarternions and octonions are collectively known as the normed division algebras. They are the only sets of numbers with which you can perform addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Wilder systems are possible – the 16-dimensional sedenions, for example – but here the normal rules break down.

Today, physics makes prolific use of three of these systems. The real numbers are ubiquitous. Complex numbers are essential in particle physics as well as quantum physics. The mathematical structure of general relativity, Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity, can be expressed elegantly by the quaternions.

The octonions stand oddly apart as the only system not to tie in with a central physical law. But why would nature map onto only three of these four number systems? “This makes one suspect that the octonions – the grandest and least understood of the four – should turn out to be important too,” says Boyle.

In truth, physicists have been thinking such thoughts since the 1970s, but the octonions have yet to fulfil their promise. Michael Duff at Imperial College London was, and still is, drawn to the octonions, but he knows many have tried and failed to decipher their role in describing reality. “The octonions became known as the graveyard of theoretical physics,” he says.

That hasn’t put off a new generation of octonion wranglers, including Nichol Furey at Humboldt University of Berlin. She likes to look at questions in physics without making any assumptions. “I try to solve problems right from scratch,” she says. “In doing so, you can often find alternate paths that earlier authors may have missed.” Now, it seems she and others might be making the beginnings of an octonion breakthrough.

Internal symmetries in quantum mechanics

To get to grips with Furey’s work, it helps to understand a concept in physics called internal symmetry. This isn’t the same as the rotational or reflectional symmetry of a snowflake. Instead, it refers to a number of more abstract properties, such as the character of certain forces and the relationships between fundamental particles. All these particles are defined by a series of quantum numbers – their mass, charge and a quantum property called spin, for instance. If a particle transforms into another particle – an electron becoming a neutrino, say – some of those numbers will change while others won’t. These symmetries define the structure of the standard model.

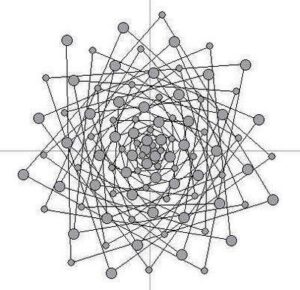

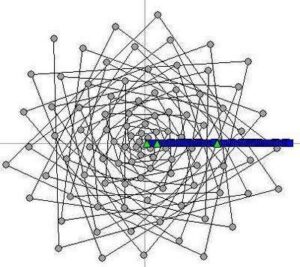

Internal symmetries are central to the quest for a grand unified theory. Physicists have already found various mathematical models that might explain how reality worked back at the time when the universe had much more energy. At these higher energies, it is thought there would have been more symmetries, meaning that some forces we now experience as distinct would have been one and the same. None of these models have managed to rope gravity into the fold: that would require an even grander “theory of everything”. But they do show, for instance, that the electromagnetic force and weak nuclear force would have been one “electroweak” force until a fraction of a second after the big bang. As the universe cooled, some of the symmetries broke, meaning this particular model would no longer apply.

Each different epoch requires a different mathematical model with a gradually reducing number of symmetries. In a sense, these models all contain each other, like a set of Russian dolls.

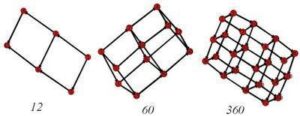

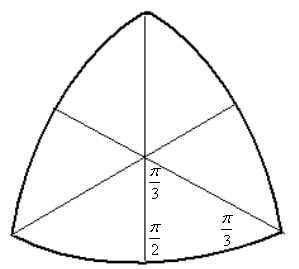

One of the most popular candidates for the outermost doll – the grand unified theory that contains all the others – is known as the spin(10) model. It has a whopping 45 symmetries. In one formulation, inside this sits the Pati-Salam model, with 21 symmetries. Then comes the left-right symmetric model, with 15 symmetries, including one known as parity, the kind of left-right symmetry that we encounter when we look in a mirror. Finally, we reach the standard model, with 12 symmetries. The reason we study each of these models is that they work; their symmetries are consistent with experimental evidence. But we have never understood what determines which symmetries fall away at each stage.

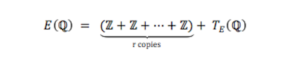

In August 2022, Furey, together with Mia Hughes at Imperial College London, showed for the first time that the division algebras, including the octonions, could provide this link. To do so, they drew on ideas Furey had years ago to translate all the mathematical symmetries and particle descriptions of various models into the language of division algebras. “It took a long time,” says Furey. The task required using the Dixon algebra, a set of numbers that allow you to combine real, complex, quaternion and octonion maths. The result was a system that describes a set of octonions specified by quaternions, which are in turn specified by complex numbers that are specified by a set of real numbers. “It’s a fairly crazy beast,” says Hughes.

It is a powerful beast, too. The new formulation exposed an intriguing characteristic of the Russian doll layers. When some numbers involved in the complex, quaternion and octonion formulations are swapped from positive to negative, or vice versa, some of the symmetries change and some don’t. Only the ones that don’t are found in the next layer down. “It allowed us to see connections between these well-studied particle models that had not been picked up on before,” says Furey. This “division algebraic reflection”, as Furey calls it, could be dictating what we encounter in the real physical universe, and – perhaps – showing us the symmetry-breaking road up to the long-sought grand unified theory.

The result is new, and Furey and Hughes haven’t yet been able to see where it may lead. “It hints that there might be some physical symmetry-breaking process that somehow depends upon these division algebraic reflections, but so far the nature of that process is fairly mysterious,” says Hughes.

Furey says the result might have implications for experiments. “We are currently investigating whether the division algebras are telling us what can and cannot be directly measured at different energy scales,” she says. It is a work in progress, but analysis of the reflections seems to suggest that there are certain sets of measurements that physicists should be able to make on particles at low energies – such as the measurement of an electron’s spin – and certain things that won’t be measurable, such as the colour charge of quarks.

Among those who work on octonions, the research is making waves. Duff says that trying to fit the standard model into octonionic language is a relatively new approach: “If it paid off, it would be very significant, so it’s worth trying.” Corinne Manogue at Oregon State University has worked with octonions for decades and has seen interest ebb and flow. “This moment does seem to be a relative high,” she says, “primarily, I think, because of Furey’s strong reputation and advocacy.

The insights from the octonions don’t stop there. Boyle has been toying with another bit of exotic maths called the “exceptional Jordan algebra”, which was invented by German physicist Pascual Jordan in the 1930s. Working with two other luminaries of quantum theory, Eugene Wigner and John von Neumann, Jordan found a set of mathematical properties of quantum theory that resisted classification and were closely related to the octonions.

Probe this exceptional Jordan algebra deeply enough and you will find it contains the mathematical structure that we use to describe Einstein’s four-dimensional space-time. What’s more, we have known for decades that within the exceptional Jordan algebra, you will find a peculiar mathematical structure that we derived through an entirely separate route and process in the early 1970s to describe the standard model’s particles and forces. In other words, this is an octonionic link between our theories of space, time, gravity and quantum theory. “I think this is a very striking, intriguing and suggestive observation,” says Boyle.

Responding to this, Boyle has dug deeper and discovered something intriguing about the way a class of particles called fermions, which includes common particles like electrons and quarks, fits into the octonion-based language. Fermions are “chiral”, meaning their mirror-image reflections – the symmetry physicists call parity – look different. This had created a problem when incorporating fermions into the octonion-based versions of the standard model. But Boyle has now found a way to fix that – and it has a fascinating spin-off. Restoring the mirror symmetry that is broken in the standard model also enables octonionic fermions to sit comfortably in the left-right symmetric model, one level further up towards the grand unified theory.

Beyond the big bang

This line of thinking might even take us beyond the grand unified theory, towards an explanation of where the universe came from. Boyle has been working with Neil Turok, his colleague at the Perimeter Institute, on what they call a “two-sheeted universe” that involves a set of symmetries known as charge, parity and time (CPT). “In this hypothesis, the big bang is a kind of mirror separating our half of the universe from its CPT mirror image on the other side of the bang,” says Boyle. The octonionic properties of fermions that sit in the left-right symmetric model are relevant in developing a coherent theory for this universe, it turns out. “I suspect that combining the octonionic picture with the two-sheeted picture of the cosmos is a further step in the direction of finding the right mathematical framework for describing nature,” says Boyle.

As with all the discoveries linking the octonions to our theories of physics so far, Boyle’s work is only suggestive. No one has yet created a fully fledged theory of physics based on octonions that makes new predictions we can test by using particle colliders, say. “There’s still nothing concrete yet: there’s nothing we can tell the experimentalists to go and look for,” says Duff. Furey agrees: “It is important to say that we are nowhere near being finished.

But Boyle, Furey, Hughes and many others are increasingly absorbed by the possibility that this strange maths really could be our best route to understanding where the laws of nature come from. In fact, Boyle thinks that the octonion-based approach could be just as fruitful as doing new experiments to find new particles. “Most people are imagining that the next bit of progress will be from some new pieces being dropped onto the table,” he says. “That would be great, but maybe we have not yet finished the process of fitting the current pieces together.”

For more such insights, log into www.international-maths-challenge.com.

*Credit for article given to Michael Brooks*