The central limit theorem – the idea that plotting statistics for a large enough number of samples from a single population will result in a normal distribution – forms the basis of the majority of the inferential statistics that students learn in advanced school-level maths courses. Because of this, it’s a concept not normally encountered until students are much older. In our work on the Framework, however, we always ask ourselves where the ideas that make up a particular concept begin. And are there things we could do earlier in school that will help support those more advanced concepts further down the educational road?

The central limit theorem is an excellent example of just how powerful this way of thinking can be, as the key ideas on which it is built are encountered by students much earlier, and with a little tweaking, they can support deeper conceptual understanding at all stages.

The key underlying concept is that of a sampling distribution, which is a theoretical distribution that arises from taking a very large number of samples from a single population and calculating a statistic – for example, the mean – for each one. There is an immediate problem encountered by students here which relates to the two possible ways in which a sample can be conceptualised. It is common for students to consider a sample as a “mini-population;” this is often known as an additive conception of samples and comes from the common language use of the word, where a free “sample” from a homogeneous block of cheese is effectively identical to the block from which it came. If students have this conception, then a sampling distribution makes no sense as every sample is functionally identical; furthermore, hypothesis tests are problematic as every random sample is equally valid and should give us a similar estimate of any population parameter.

A multiplicative conception of a sample is, therefore, necessary to understand inferential statistics; in this frame, a sample is viewed as one possible outcome from a set of possible but different outcomes. This conception is more closely related to ideas of probability and, in fact, can be built from some simple ideas of combinatorics. In a very real sense, the sampling distribution is actually the sample space of possible samples of size n from a given population. So, how can we establish a multiplicative view of samples early on so that students who do go on to advanced study do not need to reconceptualise what a sample is in order to avoid misconceptions and access the new mathematics?

One possible approach is to begin by exploring a small data set by considering the following:

“Imagine you want to know something about six people, but you only have time to actually ask four of them. How many different combinations of four people are there?”

There are lots of ways to explore this question that make it more concrete – perhaps by giving a list of names of the people along with some characteristics, such as number of siblings, hair colour, method of travel to school, and so on. Early explorations could focus on simply establishing that there are in fact 15 possible samples of size four through a systematic listing and other potentially more creative representations, but then more detailed questions could be asked that focus on the characteristics of the samples; for example, is it common that three of the people in the sample have blonde hair? Is an even split between blue and brown eyes more or less common? How might these things change if a different population of six people was used?

Additionally, there are opportunities to practise procedures within a more interesting framework; for example, if one of the characteristics was height then students could calculate the mean height for each of their samples – a chance to practise the calculation as part of a meaningful activity – and then examine this set of averages. Are they close to a particular value? What range of values are covered? How are these values clustered? Hey presto – we have our first sampling distribution without having to worry about the messy terminology and formal definitions.

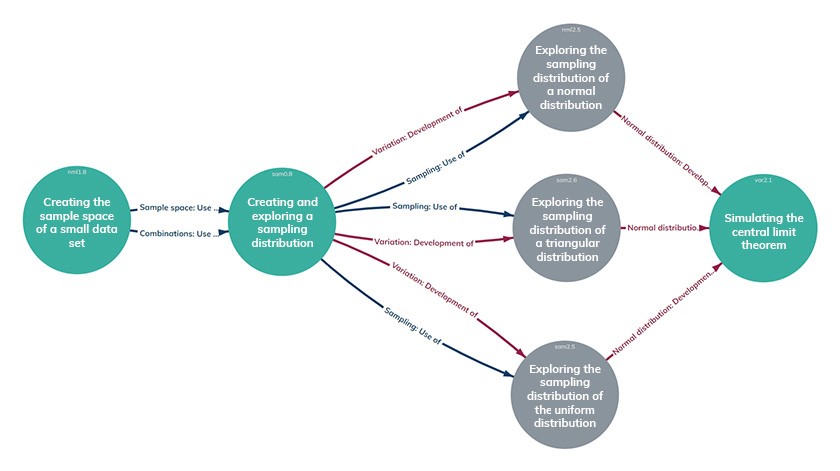

In the Cambridge Mathematics Framework, this approach is structured as exploratory work in which students play with the idea of a small sample as a combinatorics problem in order to motivate further exploration. Following this early work, they eventually created their first sampling distribution for a more realistic population and explored its properties such as shape, spread, proportions, etc. This early work lays the ground to look at sampling from some specific population distributions – uniform, normal, and triangular – to get a sense of how the underlying distribution impacts the sampling distribution. Finally, this is brought together by using technology to simulate the sampling distribution for different empirical data sets using varying sizes of samples in order to establish the concept of the central limit theorem.

While sampling distributions and the central limit theorem may well remain the preserve of more advanced mathematics courses, considering how to establish the multiplicative concept of a sample at the very beginning of students’ work on sampling may well help lay more secure foundations for much of the inferential statistics that comes later, and may even support statistical literacy for those who don’t go on to learn more formal statistical techniques.

For more insights like this, visit our website at www.international-maths-challenge.com.

Credit for the article given to Darren Macey