A maths problem previously tackled with the help of a computer, which produced a proof the size of Wikipedia, has now been cut down to size by a human. Although it is unlikely to have practical applications, the result highlights the differences between two modern approaches to mathematics: crowdsourcing and computers.

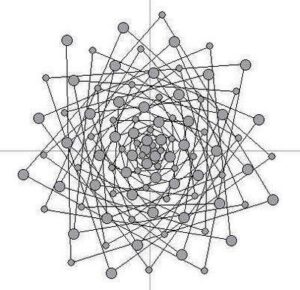

Terence Tao of the University of California, Los Angeles, has published a proof of the Erdős discrepancy problem, a puzzle about the properties of an infinite, random sequence of +1s and -1s. In the 1930s, Hungarian mathematician Paul Erdős wondered whether such a sequence would always contain patterns and structure within the randomness.

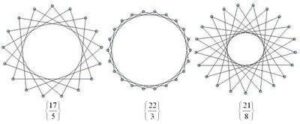

One way to measure this is by calculating a value known as the discrepancy. This involves adding up all the +1s and -1s within every possible sub-sequence. You might think the pluses and minuses would cancel out to make zero, but Erdős said that as your sub-sequences got longer, this sum would have to go up, revealing an unavoidable structure. In fact, he said the discrepancy would be infinite, meaning you would have to add forever, so mathematicians started by looking at smaller cases in the hopes of finding clues to attack the problem in a different way.

Last year, Alexei Lisitsa and Boris Konev of the University of Liverpool, UK used a computer to prove that the discrepancy will always be larger than two. The resulting proof was a 13 gigabyte file – around the size of the entire text of Wikipedia – that no human could ever hope to check.

Helping hands

Tao has used more traditional mathematics to prove that Erdős was right, and the discrepancy is infinite no matter the sequence you choose. He did it by combining recent results in number theory with some earlier, crowdsourced work.

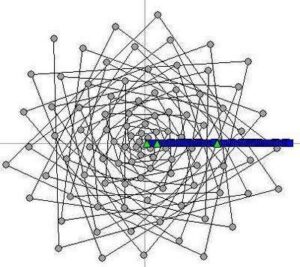

In 2010, a group of mathematicians, including Tao, decided to work on the problem as the fifth Polymath project, an initiative that allows professionals and amateurs alike to contribute ideas through SaiBlogs and wikis as part of mathematical super-brain. They made some progress, but ultimately had to give up.

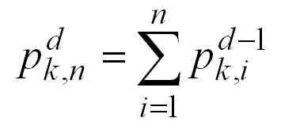

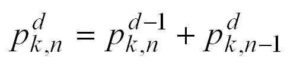

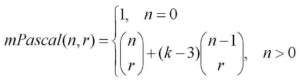

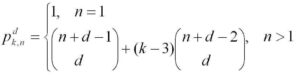

“We had figured out an interesting reduction of the Erdős discrepancy problem to a seemingly simpler problem involving a special type of sequence called a completely multiplicative function,” says Tao.

Then, in January this year, a new development in the study of these functions made Tao look again at the Erdős discrepancy problem, after a commenter on his SaiBlog pointed out a possible link to the Polymath project and another problem called the Elliot conjecture.

Not just conjecture

“At first I thought the similarity was only superficial, but after thinking about it more carefully, and revisiting some of the previous partial results from Polymath5, I realised there was a link: if one could prove the Elliott conjecture completely, then one could also resolve the Erdős discrepancy problem,” says Tao.

“I have always felt that that project, despite not solving the problem, was a distinct success,” writes University of Cambridge mathematician Tim Gowers, who started the Polymath project and hopes that others will be encouraged to participate in future. “We now know that Polymath5 has accelerated the solution of a famous open problem.”

Lisitsa praises Tao for doing what his algorithm couldn’t. “It is a typical example of high-class human mathematics,” he says. But mathematicians are increasingly turning to machines for help, a trend that seems likely to continue. “Computers are not needed for this problem to be solved, but I believe they may be useful in other problems,” Lisitsa says.

For more such insights, log into www.international-maths-challenge.com.

*Credit for article given to Jacob Aron*