The importance of mathematics in daily and professional life has been increasing with the contribution of developing technology. The level of mathematical knowledge and skills directly influence the quality standards of our individual and social life. However, mathematics the importance of which we feel in every aspect of our life is unfortunately not learned enough by many individuals for many reasons. The leading reasons regarding this issue are as follows: the abstract and hierarchical structure of mathematics, methods and strategies in learning mathematics, and the learning difficulties in mathematics. Developmental Dyscalculia (DD)/Mathematics Learning Difficulty (MLD) is a brain-based condition that negatively affects mathematics acquisition.

The mathematical performance of a student with MLD is much lower than expected for age, intelligence, and education, although there are no conditions such as intellectual disability, emotional disturbances, cultural deprivation, or lack of education. Difficulties in mathematics result from a number of cognitive and emotional factors. Math anxiety is one of the emotional factors that may severely disrupt a significant number of children and adults in learning and achievement in math.

Math anxiety is defined as “the feelings of tension and anxiety that interfere with the manipulation of numbers and the solving of mathematical problems in a wide variety of ordinary life and academic situations”. Sherard describes math anxiety as the fear of math or an intense and negative emotional response to mathematics. There are many reasons for the cause of the math anxiety. These include lack of the appropriate mathematical background of the students, study habits of memorizing formulas, problems and applications that are not related to real life, challenging and time-limited exams, lack of concrete materials, the difficulty of some subjects in mathematics, type of personality, negative approach on mathematics, lack of confidence, the approaches, feelings, and thoughts of teachers and parents on mathematics.

The negative relationship between math anxiety and math performance is an international issue. The PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) statistics measuring a wide variety of countries and cultures depict that the high level of negative correlation between math anxiety and mathematical performance is remarkable. Some studies showed that highly math-anxious individuals are worse than those with low mathematics anxiety in terms of solving mathematical problems. These differences are not typically observed in simple arithmetic operations such as 7 + 9 and 6 × 8, but it is more evident when more difficult arithmetic problems are tested.

Math anxiety is associated with cognitive information processing resources during arithmetic task performance in a developing brain. It is generally accepted that math anxiety negatively affects mathematical performance by distorting sources of working memory. The working memory is conceptualized as a limited source of cognitive systems responsible for the temporary storage and processing of information in momentary awareness.

The learning difficulties in mathematics relate to deficiencies in the central executive component of the working memory. Many studies suggest that individuals with learning difficulties in mathematics have a lack of working memory. It is stated that students with learning difficulties in mathematics use more inferior strategies than their peers for solving basic (4 + 3) and complex (16 + 8) addition and fall two years behind their peers while they fall a year behind in their peers’ working memory capacities.

Highly math-anxious individuals showed smaller working memory spans, especially when evaluated with a computationally based task. This reduced working memory capacity, when implemented simultaneously with a memory load task, resulting in a significant increase in the reaction time and errors. A number of studies showed that working memory capacity is a robust predictor of arithmetic problem-solving and solution strategies.

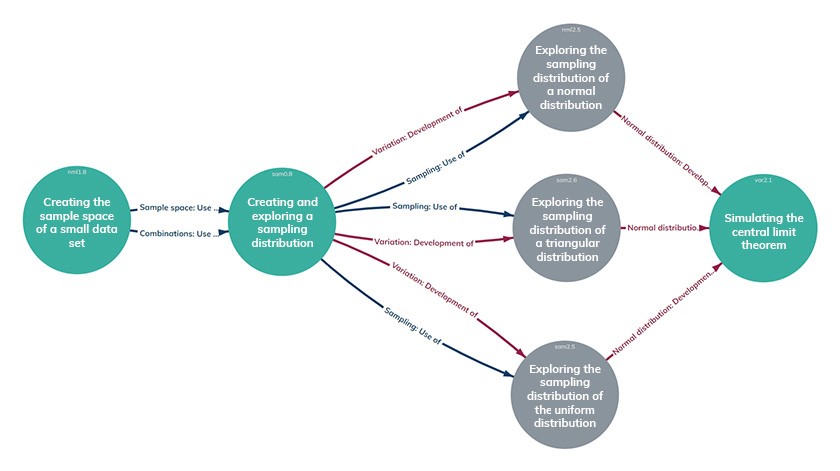

Although it is not clear to what extent math anxiety affects mathematical difficulties and how much of the experience of mathematical difficulties causes mathematical anxiety, there is considerable evidence that math anxiety affects mathematical performance that requires working memory. Figure below depicts these reciprocal relationships among math anxiety, poor math performance, and lack of working memory. The findings of the studies mentioned above, make it possible to draw this figure.

Basic numerical and mathematical skills have been crucial predictors of an individual’s vital success. When anxiety is controlled, it is seen that the mathematical performance of the students increases significantly. Hence, early identification and treatment of math anxiety is of importance. Otherwise, early anxieties can have a snowball effect and eventually lead students to avoid mathematics courses and career options for math majors. Although many studies confirm that math anxiety is present at high levels in primary school children, it is seen that the studies conducted at this level are relatively less when the literature on math anxiety is examined. In this context, this study aims to determine the dimensions of the relationship between math anxiety and mathematics achievement of third graders by their mathematics achievement levels.

Methods

The study was conducted by descriptive method. The purpose of the descriptive method is to reveal an existing situation as it is. This study aims to examine the relationship between math anxiety and mathematics achievement of third graders in primary school in terms of student achievement levels.

Participants

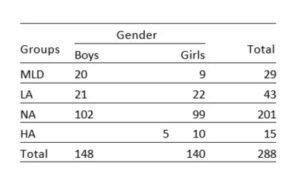

Researchers of mathematics learning difficulties (MLD) commonly use cutoff scores to determine which participants have MLD. These cutoff scores vary between -2 ss and -0.68 ss. Some researchers apply more restrictive cutoffs than others (e.g., performance below the 10th percentile or below the 35th percentile). The present study adopted the math achievement test to determine children with MLD based below the 10th percentile. The unit of analysis was third graders of an elementary school located in a low socioeconomic area. The study reached 288 students using math anxiety scale and math achievement test tools. The students were classified into four groups by their mathematics achievement test scores: math learning difficulties (0-10%), low achievers (11-25%), normal achievers (26-95%), and high achievers (96-100%).

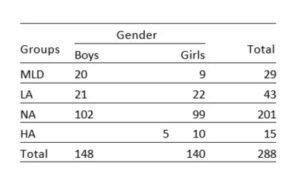

Table 1. Distribution of participants by gender and groups

Data Collection Tools

Two copyrighted survey scales, consisting of 29 items were used to construct a survey questionnaire. The first scale is the Math Anxiety Scale developed by Mutlu & Söylemez for 3rd and 4th graders with a 3-factor structure of 13 items. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient is adopted by the study to evaluate the extent to which a measurement produces reliable results at different times. The Cronbach Alpha coefficient of the scale is .75 which confirms the reliability of and internal consistency of the study. The response set was designed in accordance with the three- point Likert scale with agree, neutral, and disagree. Of the 13 items in the scale, 5 were positive and 8 were negative. Positive items were rated as 3-2-1, while negative items were rated as 1-2-3. The highest score on the scale was 39 and the lowest on the scale was 13.

The second data collection tool adopted by this study is the math achievement test for third graders developed by Fidan (2013). It has 16 items designed in accordance with the national math curriculum. Correct responses were scored one point while wrong responses were scored zero point.

Data Analysis

The study mainly utilized five statistical analyses which are descriptive analysis, independent samples t-test, Pearson product-moment correlation analysis, linear regression and ANOVA. First, an independent samples t-test was performed to determine whether there was a significant difference between the levels of math anxiety by gender. Then, a Pearson product-moment correlation analysis was performed to determine the relationship between the math anxiety and mathematics achievement of the students. After that, a linear regression analysis was performed to predict the mathematics achievement of the participants based on their math anxiety. Finally, an ANOVA was performed to determine if there was a significant difference between the math anxiety of the groups determined in terms of mathematics achievement.

Results

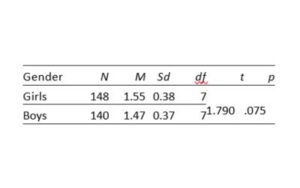

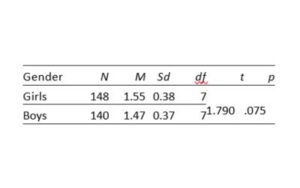

The findings of the math anxiety scores by gender of the study found no significant difference between the averages [t(286)= 1.790, p< .05]. This result shows that the math anxiety levels of girls and boys are close to each other. Since there is no difference between math anxiety scores by gender, the data in the study were combined.

Table 2. Comparison of anxiety scores by gender

There was a strong and negative correlation between math anxiety and mathematics achievement with the values of r= -0.597, n= 288, and p= .00. This result indicates that the highly math-anxious students and decreases in math anxiety were correlated with increases in rating of math achievement.

A simple linear regression was calculated to predict math achievement level based on the math anxiety. A significant regression equation was found (F(1,286)= 158.691, p< .000) with an R2 of .357. Participants’ predicted math achievement is equal to 20.153 + -6.611 when math anxiety is measured in unit. Math achievement decreased -6.611 for each unit of the math anxiety.

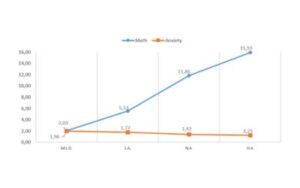

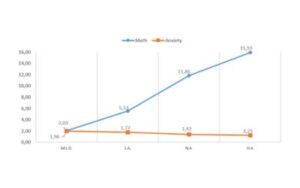

Figure below shows the relationship between the math anxiety of the children and their mathematics achievement on a group basis. Figure 1 provides us that there is a negative correlation between mathematical performance and math anxiety. The results depict that the HA group has the lowest math anxiety score, while the MLD group has the highest math anxiety.

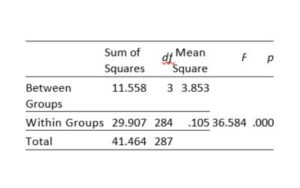

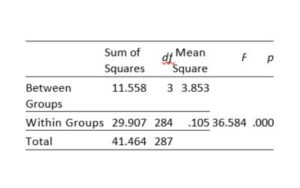

Table 3. Comparison of the mathematical anxiety scores of the groups

The table indicates that there is a statistically significant difference between groups as determined at the p<.05 level by one-way ANOVA (F(3,284)= 36.584, p= .000). Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey test indicated that the mean score for MLD group (M= 1.96, sd= 0.30) was significantly different than the NA group (M= 1.41, sd= 0.84) and HA group (M= 1.24, sd= 0.28). However, the MLD group (M= 1.96, sd= 0.30) did not significantly differ from the LA group (M= 1.76, sd= 0.27).

Discussion and Conclusion

Math anxiety is a problem that can adversely affect the academic success and employment prospects of children. Although the literature on math anxiety is largely focused on adults, recent studies have reported that some children begin to encounter math anxiety at the elementary school level. The findings of the study depict that the correlation level of math anxiety and math achievement is -.597 among students. In a meta-analysis study of Hembre and Ma, found that the level of relationship between mathematical success and math anxiety is -.34 and -.27, respectively. In a similar meta-analysis study performed in Turkey, the correlation coefficient was found to be -.44. The different occurrence of the coefficients is probably dependent on the scales used and the sample variety.

The participants of the study were classified into four groups: math learning difficulties (0-10%), low success (11-25%), normal (26-95%), and high success (96-100%) by the mathematics achievement test scores. The study compared the math anxiety scores of the groups and found no significant difference between the mean scores of the math anxiety of the lower two groups (mean of MLD math anxiety, .196; mean of LA math anxiety .177) as it was between the upper two groups (mean of NA math anxiety, .142; mean of HA math anxiety .125). This indicates that the math anxiety level of the students with learning difficulties in math does not differ from the low math students. However, a significant difference was found between the mean scores of math anxiety of the low successful and the normal group.

It may be better for some students to maintain moderate levels of math anxiety to make their learning and testing materials moderately challenging, but it can be clearly said that high math anxiety has detrimental effects on the mathematical performance of the individuals. Especially for students with learning difficulties in math, the high level of math anxiety will lead to destructive effects in many dimensions, primarily a lack of working memory.

Many of the techniques employed to reduce or eliminate the link between math anxiety and poor math performance involve addressing the anxiety rather than training math itself. Some methods for reducing math anxiety can be used in teaching mathematics. For instance, effective instruction for struggling mathematics learners includes instructional explicitness, a strong conceptual basis, cumulative review and practice, and motivators to help maintain student interest and engagement.

For more insights like this, visit our website at www.international-maths-challenge.com.

Credit for the article given to Yılmaz Mutlu