School mathematics teaching is stuck in the past. An adult revisiting the school that they attended as a child would see only superficial changes from what they experienced themselves.

Yes, in some schools they might see a room full of electronic tablets, or the teacher using a touch-sensitive, interactive whiteboard. But if we zoom in on the details – the tasks that students are actually being given to help them make sense of the subject – things have hardly changed at all.

We’ve learnt a huge amount in recent years about cognitive science – how our brains work and how people learn most effectively. This understanding has the potential to revolutionise what teachers do in classrooms. But the design of mathematics teaching materials, such as textbooks, has benefited very little from this knowledge.

Some of this knowledge is counter-intuitive, and therefore unlikely to be applied unless done so deliberately. What learners prefer to experience, and what teachers think is likely to be most effective, often isn’t what will help the most.

For example, cognitive science tells us that practising similar kinds of tasks all together generally leads to less effective learning than mixing up tasks that require different approaches.

In mathematics, practising similar tasks together could be a page of questions each of which requires addition of fractions. Mixing things up might involve bringing together fractions, probability and equations in immediate succession.

Learners make more mistakes when doing mixed exercises, and are likely to feel frustrated by this. Grouping similar tasks together is therefore likely to be much easier for the teacher to manage. But the mixed exercises give the learner important practice at deciding what method they need to use for each question. This means that more knowledge is retained afterwards, making this what is known as a “desirable difficulty”.

Cognitive science applied

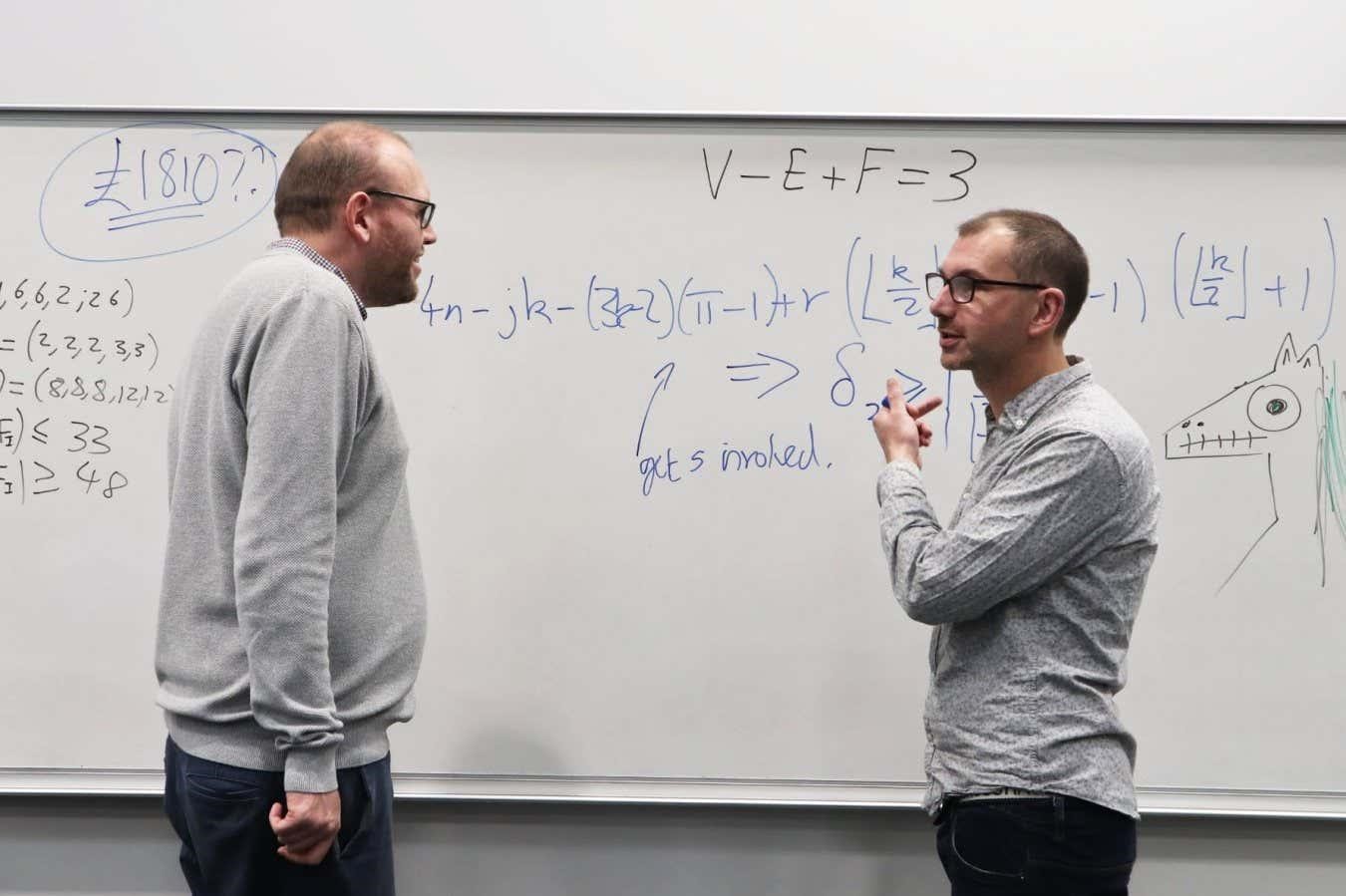

We are just now beginning to apply findings like this from cognitive science to design better teaching materials and to support teachers in using them. Focusing on school mathematics makes sense because mathematics is a compulsory subject which many people find difficult to learn.

Typically, school teaching materials are chosen by gut reactions. A head of department looks at a new textbook scheme and, based on their experience, chooses whatever seems best to them. What else can they be expected to do? But even the best materials on offer are generally not designed with cognitive science principles such as “desirable difficulties” in mind.

My colleagues and I have been researching educational designthat applies principles from cognitive science to mathematics teaching, and are developing materials for schools. These materials are not designed to look easy, but to include “desirable difficulties”.

They are not divided up into individual lessons, because this pushes the teacher towards moving on when the clock says so, regardless of student needs. Being responsive to students’ developing understanding and difficulties requires materials designed according to the size of the ideas, rather than what will fit conveniently onto a double-page spread of a textbook or into a 40-minute class period.

Switching things up

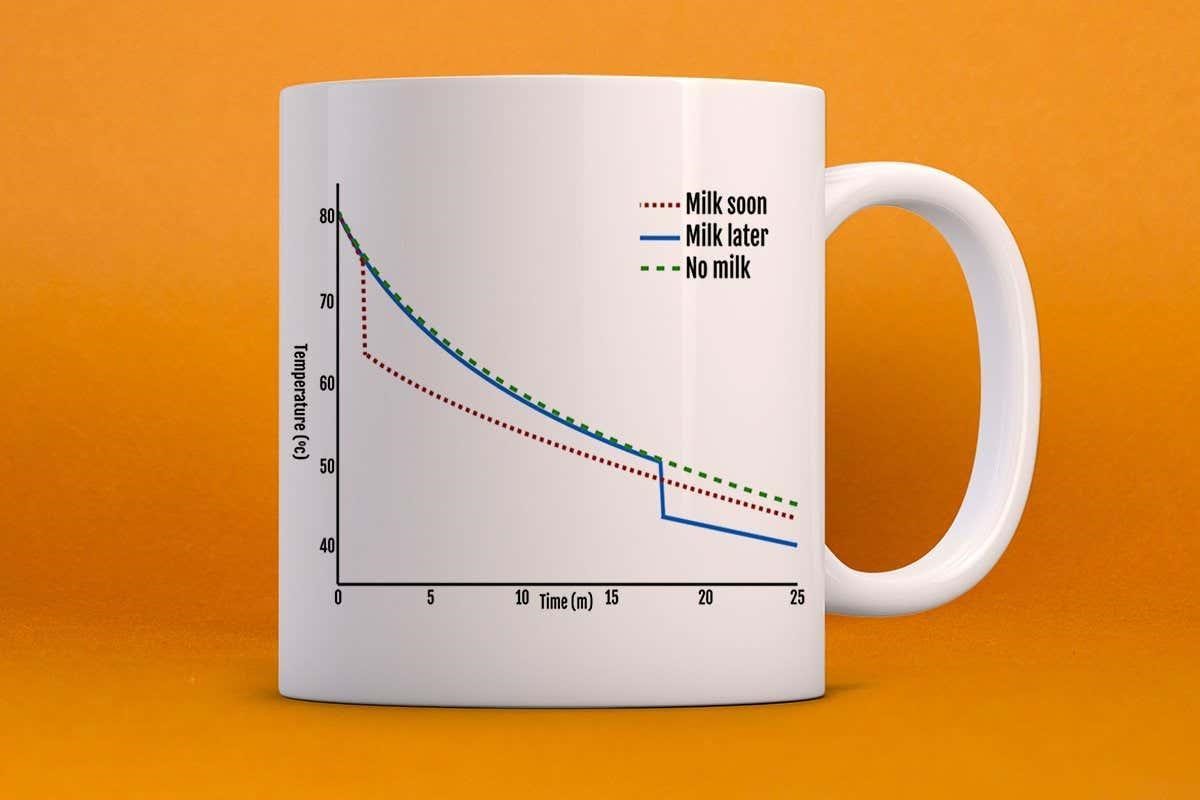

Taking an approach led by cognitive science also means changing how mathematical concepts are explained. For instance, diagrams have always been a prominent feature of mathematics teaching, but often they are used haphazardly, based on the teacher’s personal preference. In textbooks they are highly restricted, due to space constraints.

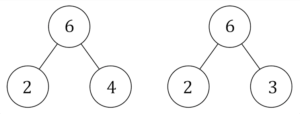

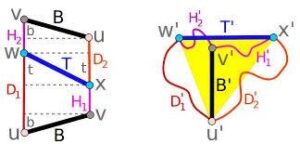

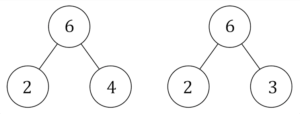

Often, similar-looking diagrams are used in different topics and for very different purposes, leading to confusion. For example, three circles connected as shown below can indicate partitioning into a sum (the “part-whole model”) or a product of prime factors.

These involve two very different operations, but are frequently represented by the same diagram. Using the same kind of diagram to represent conflicting operations (addition and multiplication) leads to learners muddling them up and becoming confused.

Number diagrams showing numbers that add together to make six and numbers that multiply to make six. Colin Foster

The “coherence principle” from cognitive science means avoiding diagrams where their drawbacks outweigh their benefits, and using diagrams and animations in a purposeful, consistent way across topics.

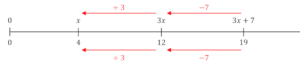

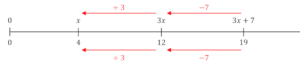

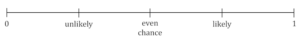

For example, number lines can be introduced at a young age and incorporated across many topic areas to bring coherence to students’ developing understanding of number. Number lines can be used to solve equations and also to represent probabilities, for instance.

Unlike with the circle diagrams above, the uses of number lines shown below don’t conflict but reinforce each other. In each case, positions on the number line represent numbers, from zero on the left, increasing to the right.

A number line used to solve an equation. Colin Foster

A number line used to show probability. Colin Foster

There are disturbing inequalities in the learning of mathematics, with students from poorer backgrounds underachieving relative to their wealthier peers. There is also a huge gender participation gap in maths, at A-level and beyond, which is taken by far more boys than girls.

Socio-economically advantaged families have always been able to buy their children out of difficulties by using private tutors, but less privileged families cannot. Better-quality teaching materials, based on insights from cognitive science, mitigate the impact for students who have traditionally been disadvantaged by gender, race or financial background in the learning of mathematics.

For more such insights, log into our website https://international-maths-challenge.com

Credit of the article given to SrideeStudio/Shutterstock