Most people have heard the famous phrase “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Now, Northwestern University researchers have used statistical physics to confirm the theory that underlies this famous axiom. The study, “Proper network randomization is key to assessing social balance,” is published in the journal Science Advances.

In the 1940s, Austrian psychologist Fritz Heider introduced social balance theory, which explains how humans innately strive to find harmony in their social circles. According to the theory, four rules—an enemy of an enemy is a friend, a friend of a friend is a friend, a friend of an enemy is an enemy and, finally, an enemy of a friend is an enemy—lead to balanced relationships.

Although countless studies have tried to confirm this theory using network science and mathematics, their efforts have fallen short, as networks deviate from perfectly balanced relationships. Hence, the real question is whether social networks are more balanced than expected according to an adequate network model.

Most network models were too simplified to fully capture the complexities within human relationships that affect social balance, yielding inconsistent results on whether deviations observed from the network model expectations are in line with the theory of social balance.

The Northwestern team, however, successfully integrated the two key pieces that make Heider’s social framework work. In real life, not everyone knows each other, and some people are more positive than others. Researchers have long known that each factor influences social ties, but existing models could only account for one factor at a time.

By simultaneously incorporating both constraints, the researchers’ resulting network model finally confirmed the famous theory some 80 years after Heider first proposed it.

The useful new framework could help researchers better understand social dynamics, including political polarization and international relations, as well as any system that comprises a mixture of positive and negative interactions, such as neural networks or drug combinations.

“We have always thought this social intuition works, but we didn’t know why it worked,” said Northwestern’s István Kovács, the study’s senior author.

“All we needed was to figure out the math. If you look through the literature, there are many studies on the theory, but there’s no agreement among them. For decades, we kept getting it wrong. The reason is because real life is complicated. We realized that we needed to take into account both constraints simultaneously: who knows whom and that some people are just friendlier than others.”

“We can finally conclude that social networks align with expectations that were formed 80 years ago,” added Bingjie Hao, the study’s first author. “Our findings also have broad applications for future use. Our mathematics allows us to incorporate constraints on the connections and the preference of different entities in the system. That will be useful for modeling other systems beyond social networks.”

Kovács is an assistant professor of Physics and Astronomy at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. Hao is a postdoctoral researcher in his laboratory.

What is social balance theory?

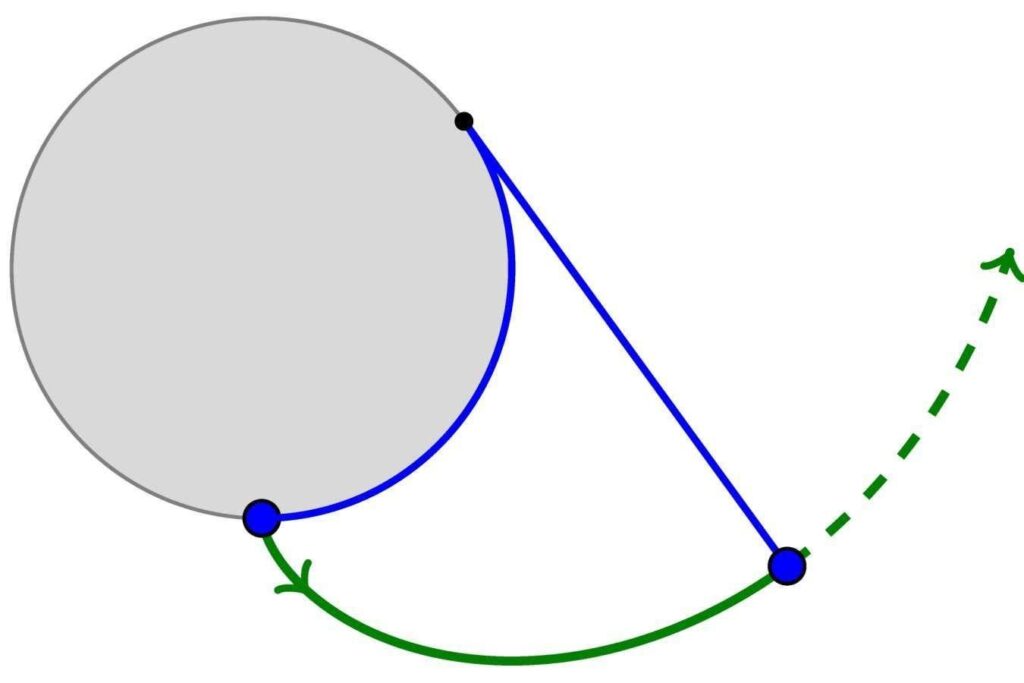

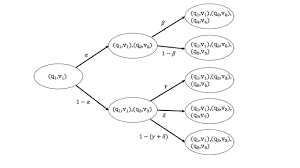

Using groups of three people, Heider’s social balance theory maintains the assumption that humans strive for comfortable, harmonious relationships.

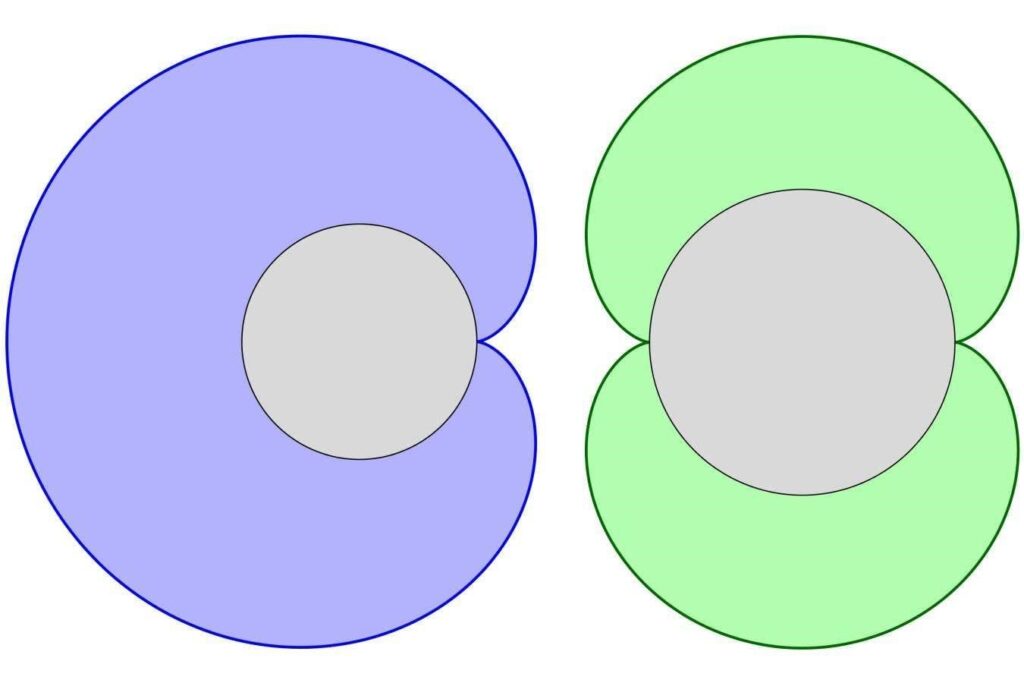

In balanced relationships, all people like each other. Or, if one person dislikes two people, those two are friends. Imbalanced relationships exist when all three people dislike each other, or one person likes two people who dislike each other, leading to anxiety and tension.

Studying such frustrated systems led to the 2021 Nobel Prize in physics to Italian theoretical physicist Giorgio Parisi, who shared the prize with climate modelers Syukuro Manabe and Klaus Hasselmann.

“It seems very aligned with social intuition,” Kovács said. “You can see how this would lead to extreme polarization, which we do see today in terms of political polarization. If everyone you like also dislikes all the people you don’t like, then that results in two parties that hate each other.”

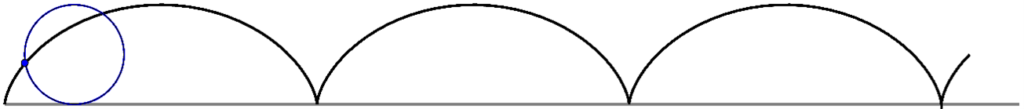

However, it has been challenging to collect large-scale data where not only friends but also enemies are listed. With the onset of Big Data in the early 2000s, researchers tried to see if such signed data from social networks could confirm Heider’s theory. When generating networks to test Heider’s rules, individual people serve as nodes. The edges connecting nodes represent the relationships among individuals.

If the nodes are not friends, then the edge between them is assigned a negative (or hostile) value. If the nodes are friends, then the edge is marked with a positive (or friendly) value. In previous models, edges were assigned positive or negative values at random, without respecting both constraints. None of those studies accurately captured the realities of social networks.

Finding success in constraints

To explore the problem, Kovács and Hao turned to four large-scale, publicly available signed network datasets previously curated by social scientists, including data from 1) user-rated comments on social news site Slashdot; 2) exchanges among Congressional members on the House floor; 3) interactions among Bitcoin traders; and 4) product reviews from consumer review site Epinions.

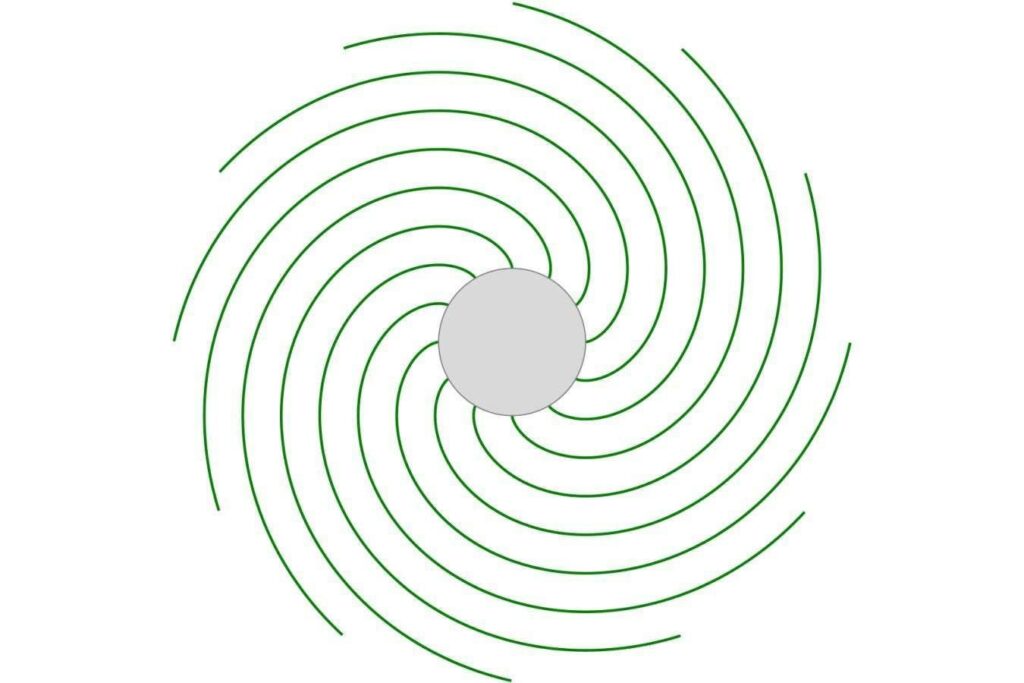

In their network model, Kovács and Hao did not assign truly random negative or positive values to the edges. For every interaction to be random, every node would need to have an equal chance of encountering one another. In real life, however, not everyone actually knows everyone else within a social network. For example, a person might not ever encounter their friend’s friend, who lives on the other side of the world.

To make their model more realistic, Kovács and Hao distributed positive or negative values based on a statistical model that describes the probability of assigning positive or negative signs to the interactions that exist. That kept the values random—but random within limits given by constraints of the network topology. In addition to who knows whom, the team took into account that some people in life are just friendlier than others. Friendly people are more likely to have more positive—and fewer hostile—interactions.

By introducing these two constraints, the resulting model showed that large-scale social networks consistently align with Heider’s social balance theory. The model also highlighted patterns beyond three nodes. It shows that social balance theory applies to larger graphlets, which involve four and possibly even more nodes.

“We know now that you need to take into account these two constraints,” Kovács said. “Without those, you cannot come up with the right mechanisms. It looks complicated, but it’s actually fairly simple mathematics.”

Insights into polarization and beyond

Kovács and Hao currently are exploring several future directions for this work. In one potential direction, the new model could be used to explore interventions aimed at reducing political polarization. But the researchers say the model could help better understand systems beyond social groups and connections among friends.

“We could look at excitatory and inhibitory connections between neurons in the brain or interactions representing different combinations of drugs to treat disease,” Kovács said. “The social network study was an ideal playground to explore, but our main interest is to go beyond investigating interactions among friends and look at other complex networks.”

For more such insights, log into our website https://international-maths-challenge.com

Credit of the article given to Northwestern University