A moment’s hesitation… Yes, a full stop here—but shouldn’t there be a comma there? Or would a hyphen be better? Punctuation can be a nuisance; it is often simply neglected. Wrong! The most recent statistical analyses paint a different picture: punctuation seems to “grow out” of the foundations shared by all the (examined) languages, and its features are far from trivial.

To many, punctuation appears as a necessary evil, to be happily ignored whenever possible. Recent analyses of literature written in the world’s current major languages require us to alter this opinion. In fact, the same statistical features of punctuation usage patterns have been observed in several hundred works written in seven, mainly Western, languages.

Punctuation, all ten representatives of which can be found in the introduction to this text, turns out to be a universal and indispensable complement to the mathematical perfection of every language studied. Such a remarkable conclusion about the role of mere commas, exclamation marks or full stops comes from an article by scientists from the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IFJ PAN) in Cracow, published in the journal Chaos, Solitons & Fractals.

“The present analyses are an extension of our earlier results on the multifractal features of sentence length variation in works of world literature. After all, what is sentence length? It is nothing more than the distance to the next specific punctuation mark— the full stop. So now we have taken all punctuation marks under a statistical magnifying glass, and we have also looked at what happens to punctuation during translation,” says Prof. Stanislaw Drozdz (IFJ PAN, Cracow University of Technology).

Two sets of texts were studied. The main analyses concerning punctuation within each language were carried out on 240 highly popular literary works written in seven major Western languages: English (44), German (34), French (32), Italian (32), Spanish (32), Polish (34) and Russian (32). This particular selection of languages was based on a criterion: the researchers assumed that no fewer than 50 million people should speak the language in question, and that the works written in it should have been awarded no fewer than five Nobel Prizes for Literature.

In addition, for the statistical validity of the research results, each book had to contain at least 1,500 word sequences separated by punctuation marks. A separate collection was prepared to observe the stability of punctuation in translation. It contained 14 works, each of which was available in each of the languages studied (two of the 98 language versions, however, were omitted due to their unavailability).

In total, authors in both collections included such writers as Conrad, Dickens, Doyle, Hemingway, Kipling, Orwell, Salinger, Woolf, Grass, Kafka, Mann, Nietzsche, Goethe, La Fayette, Dumas, Hugo, Proust, Verne, Eco, Cervantes, Sienkiewicz or Reymont.

The attention of the Cracow researchers was primarily drawn to the statistical distribution of the distance between consecutive punctuation marks. It soon became evident that in all the languages studied, it was best described by one of the precisely defined variants of the Weibull distribution.

A curve of this type has a characteristic shape: it grows rapidly at first and then, after reaching a maximum value, descends somewhat more slowly to a certain critical value, below which it reaches zero with small and constantly decreasing dynamics. The Weibull distribution is usually used to describe survival phenomena (e.g. population as a function of age), but also various physical processes, such as increasing fatigue of materials.

“The concordance of the distribution of word sequence lengths between punctuation marks with the functional form of the Weibull distribution was better the more types of punctuation marks we included in the analyses; for all marks the concordance turned out to be almost complete. At the same time, some differences in the distributions are apparent between the different languages, but these merely amount to the selection of slightly different values for the distribution parameters, specific to the language in question. Punctuation thus seems to be an integral part of all the languages studied,” notes Prof. Drozdz.

After a moment he adds with some amusement: “…and since the Weibull distribution is concerned with phenomena such as survival, it can be said with not too much tongue-in-cheek that punctuation has in its nature a literally embedded struggle for survival.”

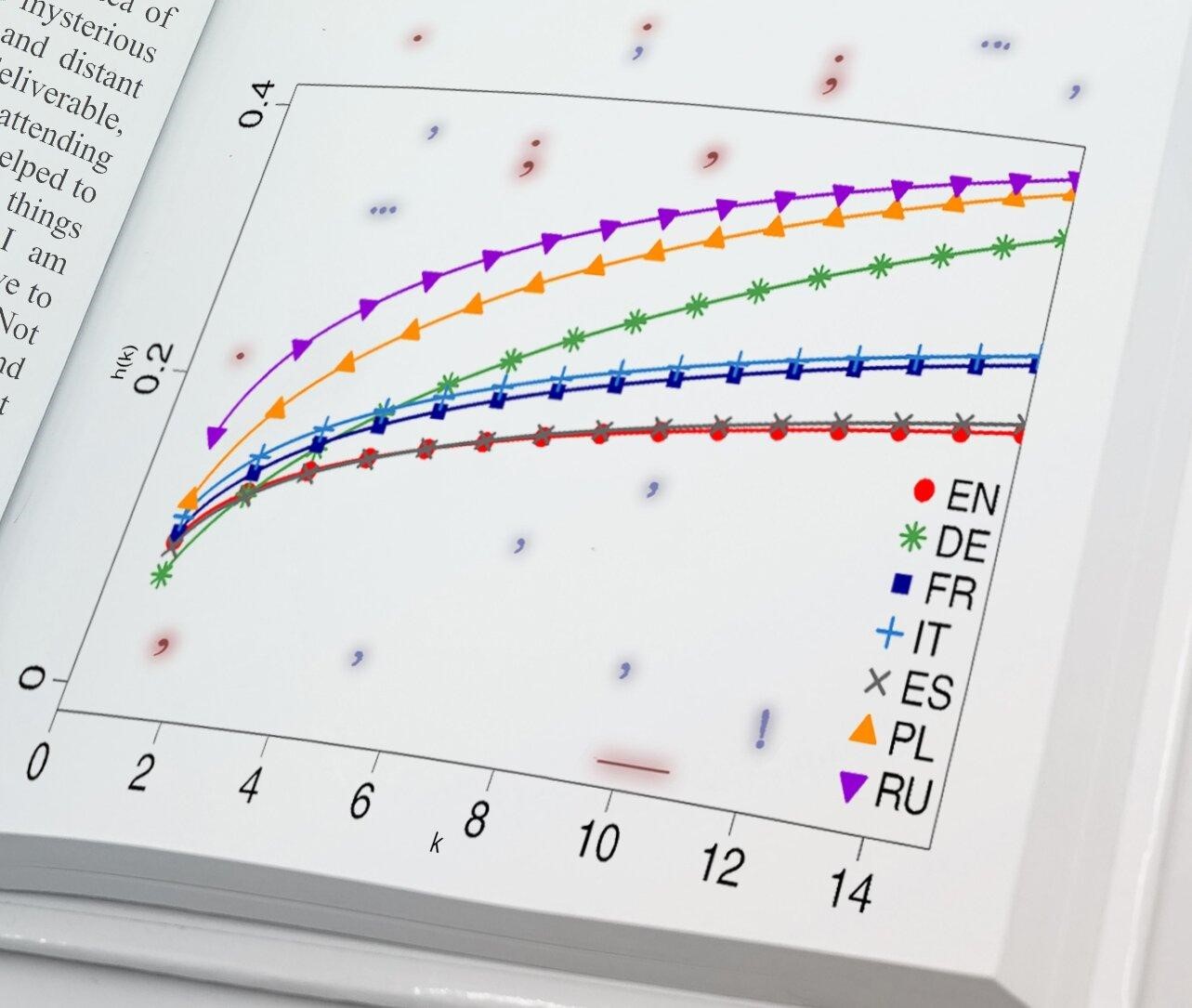

The next stage of the analyses consisted of determining the hazard function. In the case of punctuation, it describes how the conditional probability of success—i.e., the probability of the next punctuation mark—changes if no such mark has yet appeared in the analysed sequence.

The results here are clear: the language characterized by the lowest propensity to use punctuation is English, with Spanish not far behind; Slavic languages proved to be the most punctuation-dependent. The hazard function curves for punctuation marks in the six languages studied appeared to follow a similar pattern, they differed mainly in vertical shift.

German proved to be the exception. Its hazard function is the only one that intersects most of the curves constructed for the other languages. German punctuation thus seems to combine the punctuation features of many languages, making it a kind of Esperanto punctuation.

The above observation dovetails with the next analysis, which was to see whether the punctuation features of original literary works can be seen in their translations. As expected, the language most faithfully transforming punctuation from the original language to the target language turned out to be German.

In spoken communication, pauses can be justified by human physiology, such as the need to catch one’s breath or to take a moment to structure what is to be said next in one’s mind. And in written communication?

“Creating a sentence by adding one word after another while ensuring that the message is clear and unambiguous is a bit like tightening the string of a bow: it is easy at first, but becomes more demanding with each passing moment. If there are no ordering elements in the text (and this is the role of punctuation), the difficulty of interpretation increases as the string of words lengthens. A bow that is too tight can break, and a sentence that is too long can become unintelligible. Therefore, the author is faced with the necessity of ‘freeing the arrow’, i.e. closing a passage of text with some sort of punctuation mark. This observation applies to all the languages analysed, so we are dealing with what could be called a linguistic law,” states Dr. Tomasz Stanisz (IFJ PAN), first author of the article in question.

Finally, it is worth noting that the invention of punctuation is relatively recent—punctuation marks did not occur at all in old texts. The emergence of optimal punctuation patterns in modern written languages can therefore be interpreted as the result of their evolutionary advancement. However, the excessive need for punctuation is not necessarily a sign of such sophistication.

English and Spanish, contemporarily the most universal languages, appear, in the light of the above studies, to be less strict about the frequency of punctuation use. It is likely that these languages are so formalized in terms of sentence construction that there is less room for ambiguity that would need to be resolved with punctuation marks.

For more such insights, log into our website https://international-maths-challenge.com

Credit of the article given to The Henryk Niewodniczanski Institute of Nuclear Physics Polish Academy of Sciences