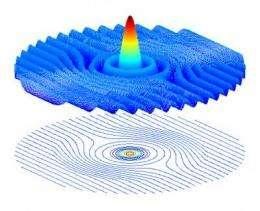

How fluids move has fascinated researchers since the birth of science.

Among the seven problems in mathematics put forward by the Clay Mathematics Institute in 2000 is one that relates in a fundamental way to our understanding of the physical world we live in.

It’s the Navier-Stokes existence and uniqueness problem, based on equations written down in the 19th century.

The solution of this prize problem would have a profound impact on our understanding of the behaviour of fluids which, of course, are ubiquitous in nature. Air and water are the most recognisable fluids; how they move and behave has fascinated scientists and mathematicians since the birth of science.

But what are the so-called Navier-Stokes equations? What do they describe?

The equations

In order to understand the Navier-Stokes equations and their derivation we need considerable mathematical training and also a sound understanding of basic physics.

Without that, we must draw upon some very simple basics and talk in terms of broad generalities – but that should be sufficient to give the reader a sense of how we arrive at these fundamental equations, and the importance of the questions.

From this point, I’ll refer to the Navier-Stokes equations as “the equations”.

The equations governing the motion of a fluid are most simply described as a statement of Newton’s Second Law of Motion as it applies to the movement of a mass of fluid (whether that be air, water or a more exotic fluid). Newton’s second law states that:

Mass x Acceleration = Force acting on a body

For a fluid the “mass” is the mass of the fluid body; the “acceleration” is the acceleration of a particular fluid particle; the “forces acting on the body” are the total forces acting on our fluid.

Without going into full details, it’s possible to state here that Newton’s Second Law produces a system of differential equations relating rates of change of fluid velocity to the forces acting on the fluid. We require one other physical constraint to be applied on our fluid, which can be most simply stated as:

Mass is conserved! – i.e. fluid neither appears nor disappears from our system.

The solution

Having a sense of what the Navier-Stokes equations are allows us to discuss why the Millennium Prize solution is so important. The prize problem can be broken into two parts. The first focuses on the existence of solutions to the equations. The second focuses on whether these solutions are bounded (remain finite).

It’s not possible to give a precise mathematical description of these two components so I’ll try to place the two parts of the problem in a physical context.

1) For a mathematical model, however complicated, to represent the physical world we are trying to understand, the model must first have solutions.

At first glance, this seems a slightly strange statement – why study equations if we are not sure they have solutions? In practice we know many solutions that provide excellent agreement with many physically relevant and important fluid flows.

But these solutions are approximations to the solutions of the full Navier-Stokes equations (the approximation comes about because there is, usually, no simple mathematical formulae available – we must resort to solving the equations on a computer using numerical approximations).

Although we are very confident that our (approximate) solutions are correct, a formal mathematical proof of the existence of solutions is lacking. That provides the first part of the Millennium Prize challenge.

2) The second part asks whether the solutions of the Navier-Stokes equations can become singular (or grow without limit).

Again, a lot of mathematics is required to explain this. But we can examine why this is an important question.

There is an old saying that “nature abhors a vacuum”. This has a modern parallel in the assertion by physicist Stephen Hawking, while referring to black holes, that “nature abhors a naked singularity”. Singularity, in this case, refers to the point at which the gravitational forces – pulling objects towards a black hole – appear (according to our current theories) to become infinite.

In the context of the Navier-Stokes equations, and our belief that they describe the movement of fluids under a wide range of conditions, a singularity would indicate we might have missed some important, as yet unknown, physics. Why? Because mathematics doesn’t deal in infinites.

The history of fluid mechanics is peppered with solutions of simplified versions of the Navier-Stokes equations that yield singular solutions. In such cases, the singular solutions have often hinted at some new physics previously not considered in the simplified models.

Identifying this new physics has allowed researchers to further refine their mathematical models and so improve the agreement between model and reality.

If, as many believe, the Navier-Stokes equations do posses singular solutions then perhaps the next Millennium Prize will go to the person that discovers just what new physics is required to remove the singularity.

Then nature can, as all fluid mechanists already do, come to delight in the equations handed down to us by Claude-Louis Navier and George Gabriel Stokes.

For more such insights, log into www.international-maths-challenge.com.

*Credit for article given to Jim Denier*