Do you know someone who knows someone? We have all played this game, often to be amazed that despite the extreme scale of human society, random people can be linked through very small chains of acquaintances—typically, around six. Recently, a group of researchers from across the globe discovered that this magic of six degrees can be explained mathematically. The intriguing phenomenon, they show, is linked to another social experience we all know too well—the struggle of cost vs. benefit in establishing new social ties.

In 1967, a farmer in Omaha, Nebraska received a peculiar letter in his mailbox. The sender was Prof. Stanley Milgram, of Harvard University, and the intended recipient was one of his peers. “If you happen to know this person,” the message read, “please forward this letter to him.”

Of course, the chances of such a direct acquaintance across such a vast social and geographical distance—from Boston to Omaha—were extremely slim, and therefore, the letter further requested that if the recipient didn’t know the intended addressee, they should forward the letter to someone who might.

This letter was one of about 300 identical packages sent with similar instructions. The 300 independent letters began circulating across the United States in pursuit of a social pathway linking “Joe” from the farmlands of middle America with the academic hub of the East Coast. Not all letters made it through, but the ones that did recorded, for the first time experimentally, the familiar social paths—a friend of a friend of a friend—that connect American society.

Quite surprisingly, the paths were found to be extremely short. In a society of hundreds of millions of individuals, the experiment found that it only takes about six handshakes to bridge between two random people. Indeed, Milgram’s experiment confirmed what many of us sense intuitively, that we live in a small world, divided by a mere six degrees of separation.

As groundbreaking as it was, Milgram’s experiment was also shaky. For example, it did not count the letters that didn’t reach their final destination. Most letters never reached their destination in Boston. The few letters that actually did arrived through six steps on average. His findings, however, were reaffirmed in a series of more systematic studies: for example, the millions of users of Facebook are on average five to six clicks apart from one another. Similar distances were also measured across 24,000 email users, actor networks, scientific collaboration networks, the Microsoft Messenger network and many others. Six degrees kept coming up.

Hence, social networks of vastly different scale and context tend to feature extremely short pathways. And most importantly, they seem to universally favour the magic number of six. But why?

A recent paper published in Physical Review X by collaborators from Israel, Spain, Italy, Russia, Slovenia and Chile, shows that simple human behaviour—weighing the costs and benefits of social ties—may uncover the roots of this intriguing phenomenon.

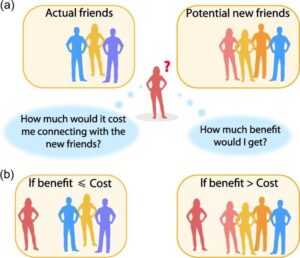

Consider individuals in a social network. Naturally, they wish to gain prominence by navigating the network and seeking strategic ties. The objective is not simply to pursue a large number of connections, but to obtain the right connections—ones that place the individual in a central network position. For example, seeking a junction that bridges between many pathways, and hence funnels much of the flow of information in the network.

Of course, such centrality in the network, while offering extremely valuable social capital, does not come for free. Friendship has a cost. It requires constant maintenance.

As a result, the research shows, social networks, whether on or offline, are a dynamic beehive of individuals constantly playing the cost-benefit game, severing connections on the one hand, and establishing new ones on the other. It’s a constant buzz driven by the ambition for social centrality. At the end, when this tug-of-war reaches an equilibrium, all individuals have secured their position in the network, a position that best balances between their drive for prominence and their limited budget for new friendships.

“When we did the math,” says Prof. Baruch Barzel, one of the paper’s lead authors, “we discovered an amazing result: this process always ends with social paths centered around the number six. This is quite surprising. We need to understand that each individual in the network acts independently, without any knowledge or intention about the network as a whole. But still, this self-driven game shapes the structure of the entire network. It leads to the small world phenomenon, and to the recurring pattern of six degrees,” adds Prof. Barzel.

The short paths characterizing social networks are not merely a curiosity. They are a defining feature of the network’s behaviour. Our ability to spread information, ideas and fads that sweep through society is deeply ingrained in the fact that it only requires a few hops to link between seemingly unrelated individuals.

Of course, not only do ideas spread through social connections. Viruses and other pathogens use them, as well. The grave consequences of this social connectedness were witnessed firsthand with the rapid spread of the COVID pandemic that demonstrated to us all the power of six degrees. Indeed, within six infection cycles, a virus can cross the globe.

“But on the upside,” adds Prof. Barzel, “this collaboration is a great example of how six degrees can play in our favour. How else would a team from six countries around the world come together? This is truly six degrees in action!”

For more such insights, log into our website https://international-maths-challenge.com

Credit of the article given to Bar-Ilan University