Everyone knows that arithmetic is true: 2 + 2 = 4.

But surprisingly, we don’t know why it’s true.

By stepping outside the box of our usual way of thinking about numbers, my colleagues and I have recently shown that arithmetic has biological roots and is a natural consequence of how perception of the world around us is organized.

Our results explain why arithmetic is true and suggest that mathematics is a realization in symbols of the fundamental nature and creativity of the mind.

Thus, the miraculous correspondence between mathematics and physical reality that has been a source of wonder from the ancient Greeks to the present—as explored in astrophysicist Mario Livio’s book “Is God a Mathematician?”—suggests the mind and world are part of a common unity.

Why is arithmetic universally true?

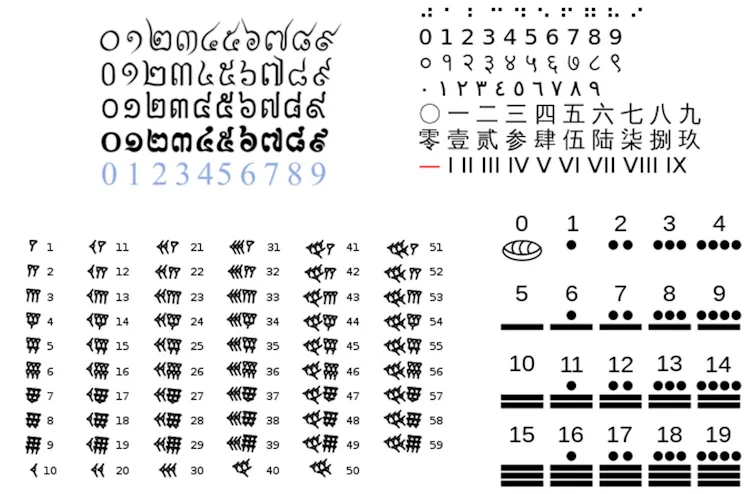

Humans have been making symbols for numbers for more than 5,500 years. More than 100 distinct notation systems are known to have been used by different civilizations, including Babylonian, Egyptian, Etruscan, Mayan and Khmer.

The remarkable fact is that despite the great diversity of symbols and cultures, all are based on addition and multiplication. For example, in our familiar Hindu-Arabic numerals: 1,434 = (1 x 1000) + (4 x 100) + (3 x 10) + (4 x 1).

Why have humans invented the same arithmetic, over and over again? Could arithmetic be a universal truth waiting to be discovered?

To unravel the mystery, we need to ask why addition and multiplication are its fundamental operations. We recently posed this question and found that no satisfactory answer—one that met standards of scientific rigor—was available from philosophy, mathematics or the cognitive sciences.

The fact that we don’t know why arithmetic is true is a critical gap in our knowledge. Arithmetic is the foundation for higher mathematics, which is indispensable for science.

Consider a thought experiment. Physicists in the future have achieved the goal of a “theory of everything” or “God equation.” Even if such a theory could correctly predict all physical phenomena in the universe, it would not be able to explain where arithmetic itself comes from or why it is universally true.

Answering these questions is necessary for us to fully understand the role of mathematics in science.

Bees provide a clue

We proposed a new approach based on the assumption that arithmetic has a biological origin.

Many non-human species, including insects, show an ability for spatial navigation which seems to require the equivalent of algebraic computation. For example, bees can take a meandering journey to find nectar but then return by the most direct route, as if they can calculate the direction and distance home.

How their miniature brain (about 960,000 neurons) achieves this is unknown. These calculations might be the non-symbolic precursors of addition and multiplication, honed by natural selection as the optimal solution for navigation.

Arithmetic may be based on biology and special in some way because of evolution’s fine-tuning.

Stepping outside the box

To probe more deeply into arithmetic, we need to go beyond our habitual, concrete understanding and think in more general and abstract terms. Arithmetic consists of a set of elements and operations that combine two elements to give another element.

In the universe of possibilities, why are the elements represented as numbers and the operations as addition and multiplication? This is a meta-mathematical question—a question about mathematics itself that can be addressed using mathematical methods.

In our research, we proved that four assumptions—monotonicity, convexity, continuity and isomorphism—were sufficient to uniquely identify arithmetic (addition and multiplication over the real numbers) from the universe of possibilities.

- Monotonicityis the intuition of “order preserving” and helps us keep track of our place in the world, so that when we approach an object it looms larger but smaller when we move away.

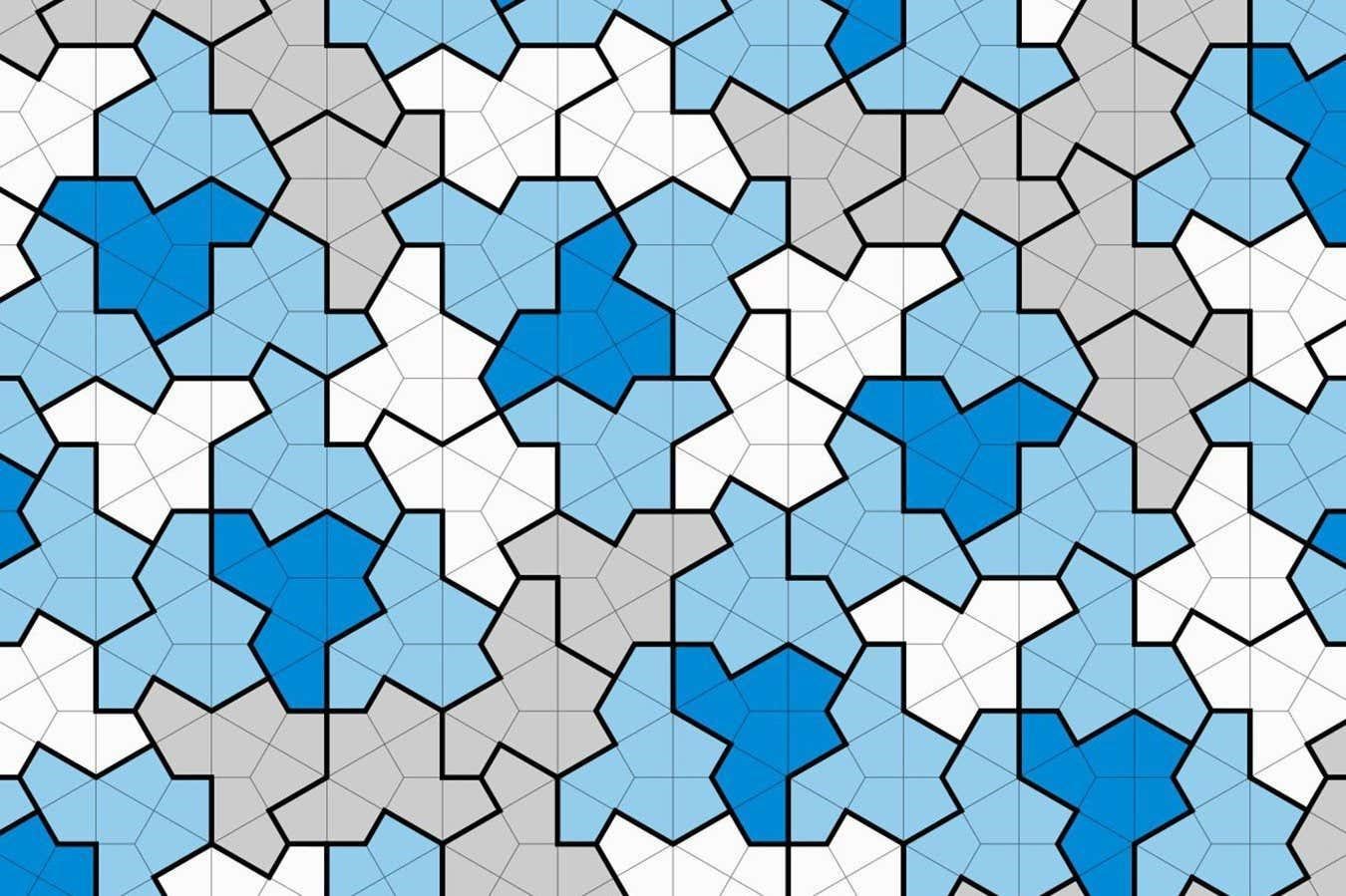

- Convexityis grounded in intuitions of “betweenness.” For example, the four corners of a football pitch define the playing field even without boundary lines connecting them.

- Continuitydescribes the smoothness with which objects seem to move in space and time.

- Isomorphismis the idea of sameness or analogy. It’s what allows us to recognize that a cat is more similar to a dog than to a rock.

Thus, arithmetic is special because it is a consequence of these purely qualitative conditions. We argue that these conditions are principles of perceptual organization that shape how we and other animals experience the world—a kind of “deep structure” in perception with roots in evolutionary history.

In our proof, they act as constraints to eliminate all possibilities except arithmetic—a bit like how a sculptor’s work reveals a statue hidden in a block of stone.

What is mathematics?

Taken together, these four principles structure our perception of the world so that our experience is ordered and cognitively manageable. They are like colored spectacles that shape and constrain our experience in particular ways.

When we peer through these spectacles at the abstract universe of possibilities, we “see” numbers and arithmetic.

Thus, our results show that arithmetic is biologically based and a natural consequence of how our perception is structured.

Although this structure is shared with other animals, only humans have invented mathematics. It is humanity’s most intimate creation, a realization in symbols of the fundamental nature and creativity of the mind.

In this sense, mathematics is both invented (uniquely human) and discovered (biologically based). The seemingly miraculous success of mathematics in the physical sciences hints that our mind and the world are not separate, but part of a common unity.

The arc of mathematics and science points toward nondualism, a philosophical concept that describes how the mind and the universe as a whole are connected, and that any sense of separation is an illusion. This is consistent with many spiritual traditions (Taoism, Buddhism) and Indigenous knowledge systems such as mātauranga Māori.

For more such insights, log into our website https://international-maths-challenge.com

Credit of the article given to Randolph Grace, The Conversation