Relating mathematics to questions that are relevant to many students can help address its image problem, argues Eugenia Cheng.

Mathematics has an image problem: far too many people are put off it and conclude that the subject just isn’t for them. There are many issues, including the curriculum, standardised tests and constraints placed on teachers. But one of the biggest problems is how maths is presented, as cold and dry.

Attempts at “real-life” applications are often detached from our daily lives, such as arithmetic problems involving a ludicrous number of watermelons or using a differential equation to calculate how long a hypothetical cup of coffee will take to cool.

I have a different approach, which is to relate abstract maths to questions of politics and social justice. I have taught fairly maths-phobic art students in this way for the past seven years and have seen their attitudes transformed. They now believe maths is relevant to them and can genuinely help them in their everyday lives.

At a basic level, maths is founded on logic, so when I am teaching the principles of logic, I use examples from current events rather than the old-fashioned, detached type of problem. Instead of studying the logic of a statement like “all dogs have four legs”, I might discuss the (also erroneous) statement “all immigrants are illegal”.

But I do this with specific mathematical structures, too. For example, I teach a type of structure called an ordered set, which is a set of objects subject to an order relation such as “is less than”. We then study functions that map members of one ordered set to members of another, and ask which functions are “order-preserving”. A typical example might be the function that takes an ordinary number and maps it to the number obtained from multiplying by 2. We would then say that if x < y then also 2x < 2y, so the function is order-preserving. By contrast the function that squares numbers isn’t order-preserving because, for example, -2 < -1, but (-2)2 > (-1)2. If we work through those squaring operations, we get 4 and 1.

However, rather than sticking to this type of dry mathematical example, I introduce ones about issues like privilege and wealth. If we think of one ordered set with people ordered by privilege, we can make a function to another set where the people are now ordered by wealth instead. What does it mean for that to be order-preserving, and do we expect it to be so? Which is to say, if someone is more privileged than someone else, are they automatically more wealthy? We can also ask about hours worked and income: if someone works more hours, do they necessarily earn more? The answer there is clearly no, but then we go on to discuss whether we think this function should be order-preserving or not, and why.

My approach is contentious because, traditionally, maths is supposed to be neutral and apolitical. I have been criticised by people who think my approach will be off-putting to those who don’t care about social justice; however, the dry approach is off-putting to those who do care about social justice. In fact, I believe that all academic disciplines should address our most important issues in whatever way they can. Abstract maths is about making rigorous logical arguments, which is relevant to everything. I don’t demand that students agree with me about politics, but I do ask that they construct rigorous arguments to back up their thoughts and develop the crucial ability to analyse the logic of people they disagree with.

Maths isn’t just about numbers and equations, it is about studying different logical systems in which different arguments are valid. We can apply it to balls rolling down different hills, but we can also apply it to pressing social issues. I think we should do both, for the sake of society and to be more inclusive towards different types of student in maths education.

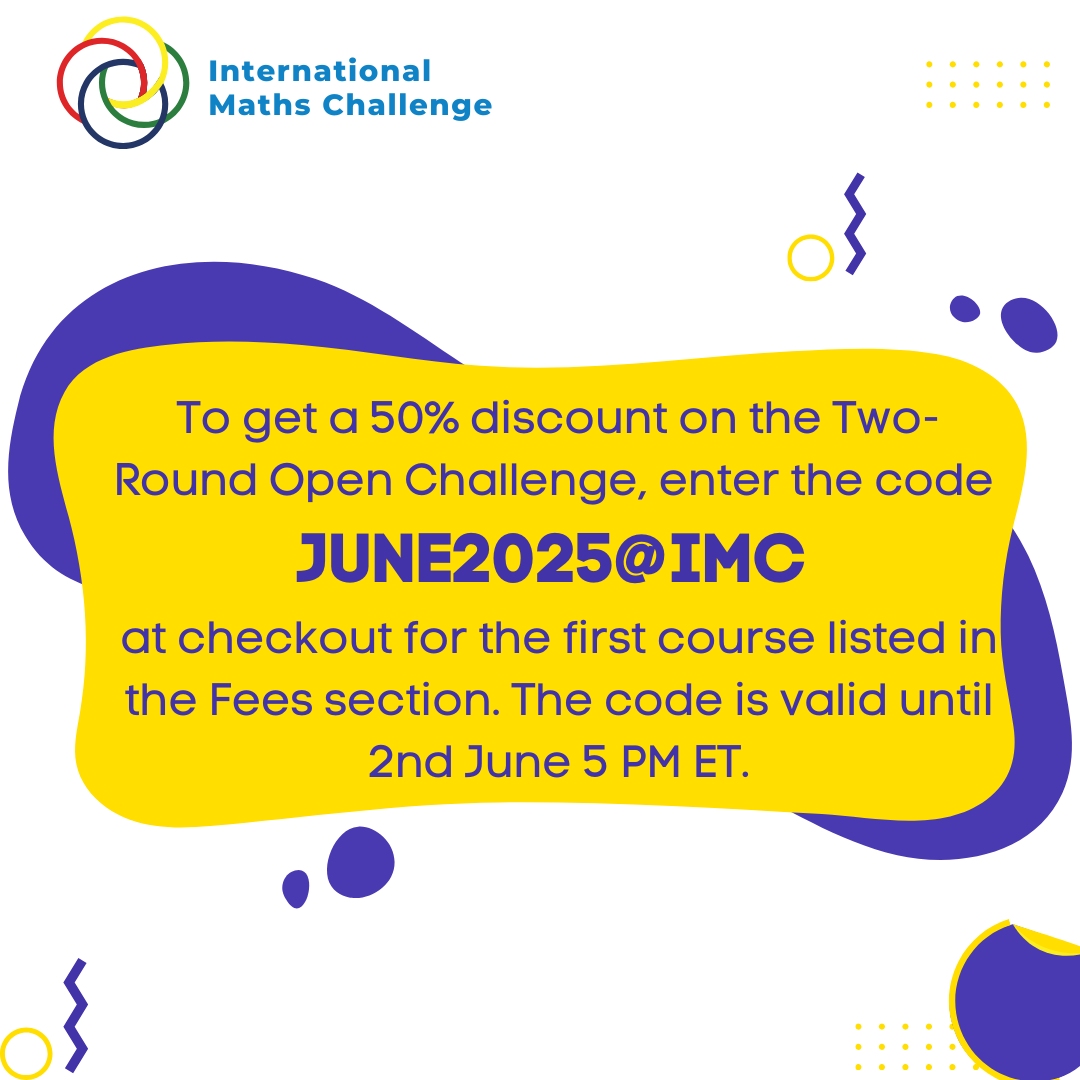

For more such insights, log into www.international-maths-challenge.com.

*Credit for article given to Eugenia Cheng*