In many traditions, Biedermann’s Dictionary of Symbols tells us, “the tree was widely seen as the axis mundi around which the cosmos is organized” and, as mentioned in a previous post, has been widely used to describe the relationship between mathematics and other sciences. Mathematics itself, like many subjects, is often portrayed as a tree whose sub-topics make up branches that continue to grow and bifurcate.

Some recent articles have take a more postmodern perspective on using the tree metaphor to describe mathematics.

Dan Kennedy ‘s “Climbing around on the Tree of Mathematics,” (full text here) and Greg McColm’s “A Metaphor for Mathematics Education” are two recent articles that make arguments by analogy about what mathematics is and how it should be taught. In Kennedy’s argument, mathematics is a tree, while in McColm’s it is a vine – both are organic, growing, and branching. What distinguishes these two uses of metaphor from traditional tree analogies is that both authors are not at all suggesting that we can stand back and survey the structure as a whole and understand how all its parts are related. The ability to provide a comprehensive view of the subject, to make it surveyable, was the raison-d’être of metaphors like the “Tree of Science.” Instead of using the metaphor this way, both authors suggest that we think of ourselves as part of the growing structure – as climbers and gardeners who cannot see the complex organic whole, but who can explore and tend to our small part of it. In these descriptions, natural forms like trees and plants, once metaphors for simplicity and comprehensibility, now provide metaphors for complexity.

Up in the Tree of Mathematics, Kennedy suggests that working mathematicians are labouring at extending its outer branches. This is where the view is best, where the fruit is found, and where the beauty of mathematics can be seen most clearly. School Mathematics is part of the trunk, the solid, oldest, stable part of the tree, and math teachers spend their time helping students climb the trunk, hoping that some may one day reach its outer branches. Unfortunately, the difficulty of the trunk prevents most people from ever climbing beyond it. Kennedy suggests that we should be less concerned with the trunk than with the branches, and that technology can provide a ladder to assist the climb.

McColm’s Mathematical Vine is not mathematics itself, but a structure that clings to the underlying reality of mathematical truth. Mathematics, in this analogy, is like a hidden tower, whose shape can only be seen by looking at the vine that has taken shape around it. Like in Kennedy’s analogy, working mathematicians are the caretakers who help the structure grow. For McColm, this analogy emphasizes the importance of mathematics education – a process of strengthening the vine so that it may continue to grow. Perhaps because his audience is primarily post-secondary researchers, he does not advocate finding shortcuts to “higher” views, but rather suggests that education be promoted through “tending to the vine” – clarifying mathematics and strengthening connections between different branches.

Although they suggest more of a structure at play, rather that a stable unified whole, organic metaphors like those used by McColm and Kennedy continue to suggest a natural unity among the various parts of mathematics. In that sense they are still rooted (or centered), and, although they have somewhat destabilized the tree analogy, they haven’t quite deconstructed it. They have not, for example, gone quite as far as Wittgenstein, who seemed to suggest that metaphors that attempt to link the subjects of mathematics in a defining way like this are misguided. In his view, as described by Ackerman (1988, p. 115):

mathematics is an assemblage of language games, having no sharp and uniform external boundary, with potentially confusing and criss-crossing subdisciplines held together by an internal network of analogous proof techniques.

It is easy to appreciate how some climbers in Kennedy’s trees and McColm’s vines end up like the protagonist in Roz Chast’s cartoon “Falling off the Math Cliff”, where step 1 is “A boy begins his wondrous journey,” and step 8 is “The plummet.”

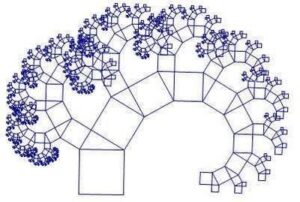

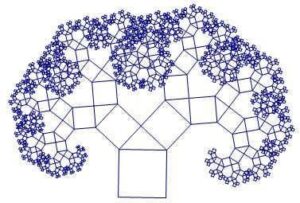

The images in this post are “Pythagoras Tree” fractals, made using GSP.

For more such insights, log into www.international-maths-challenge.com.

*Credit for article given to dan.mackinnon*