If you want your cup of tea to stay as hot as possible, should you put milk in immediately, or wait until you are ready to drink it? Katie Steckles does the sums.

Picture the scene: you are making a cup of tea for a friend who is on their way and won’t be arriving for a little while. But – disaster – you have already poured hot water onto a teabag! The question is, if you don’t want their tea to be too cold when they come to drink it, do you add the cold milk straight away or wait until your friend arrives?

Luckily, maths has the answer. When a hot object like a cup of tea is exposed to cooler air, it will cool down by losing heat. This is the kind of situation we can describe using a mathematical model – in this case, one that represents cooling. The rate at which heat is lost depends on many factors, but since most have only a small effect, for simplicity we can base our model on the difference in temperature between the cup of tea and the cool air around it.

A bigger difference between these temperatures results in a much faster rate of cooling. So, as the tea and the surrounding air approach the same temperature, the heat transfer between them, and therefore cooling of the tea, slows down. This means that the crucial factor in this situation is the starting condition. In other words, the initial temperature of the tea relative to the temperature of the room will determine exactly how the cooling plays out.

When you put cold milk into the hot tea, it will also cause a drop in temperature. Your instinct might be to hold off putting milk into the tea, because that will cool it down and you want it to stay as hot as possible until your friend comes to drink it. But does this fit with the model?

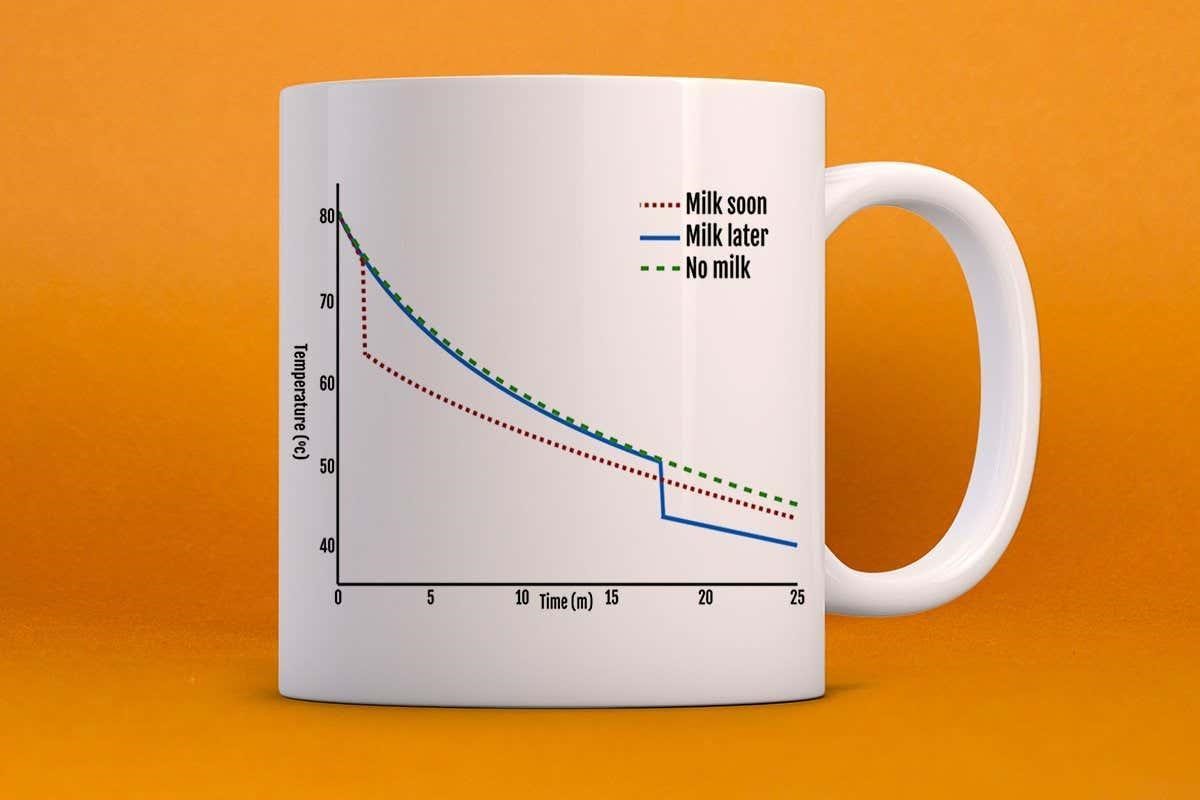

Let’s say your tea starts off at around 80°C (176°F): if you put milk in straight away, the tea will drop to around 60°C (140°F), which is closer in temperature to the surrounding air. This means the rate of cooling will be much slower for the milky tea when compared with a cup of non-milky tea, which would have continued to lose heat at a faster rate. In either situation, the graph (pictured above) will show exponential decay, but adding milk at different times will lead to differences in the steepness of the curve.

Once your friend arrives, if you didn’t put milk in initially, their tea may well have cooled to about 55°C (131°F) – and now adding milk will cause another temperature drop, to around 45°C (113°F). By contrast, the tea that had milk put in straight away will have cooled much more slowly and will generally be hotter than if the milk had been added at a later stage.

Mathematicians use their knowledge of the rate at which objects cool to study the heat from stars, planets and even the human body, and there are further applications of this in chemistry, geology and architecture. But the same mathematical principles apply to them as to a cup of tea cooling on your table. Listening to the model will mean your friend’s tea stays as hot as possible.

For more such insights, log into www.international-maths-challenge.com.

*Credit for article given to Katie Steckles*