Australian students’ performance and engagement in mathematics is an ongoing issue.

International studies show Australian students’ mean performance in maths has steadily declined since 2003. The latest Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2018 showed only 10% of Australian teenagers scored in the top two levels, compared to 44% in China and 37% in Singapore.

Despite attempts to reform how we teach maths, it is unlikely students’ performance will improve if they are not engaging with their lessons.

What teachers, parents, and policymakers may not be aware of is research shows students are using “non-thinking behaviours” to avoid engaging with maths.

That is, when your child says they didn’t do anything in maths today, our research shows they’re probably right.

What are non-thinking behaviours?

There are four main non-thinking behaviours. These are:

- slacking: where there is no attempt at a task. The student may talk or do nothing

- stalling: where there is no real attempt at a task. This may involve legitimate off-task behaviours, such as sharpening a pencil

- faking: where a student pretends to do a task, but achieves nothing. This may involve legitimate on-task behaviours such as drawing pictures or writing numbers

- mimicking: this includes attempts to complete a task and can often involve completing it. It involves referring to others or previous examples.

Peter Liljedahl studied Canadian maths lessons in all years of school, over 15 years. This research found up to 80% of students exhibit non-thinking behaviours for 100% of the time in a typical hour-long lesson.

The most common behaviour was mimicking (53%), reflecting a trend of the teacher doing all the thinking, rather than the students.

It also found when students were given “now you try one” tasks (a teacher demonstrates something, then asks students to try it), the majority of students engaged in non-thinking behaviours.

Australian students are ‘non-thinking’ too

Tracey Muir conducted a smaller-scale study in 2021 with a Year ¾ class.

Some 63% of students were observed engaged in non-thinking behaviours, with slacking and stalling (54%) being the most common. These behaviours included rubbing out, sharpening pencils, and playing with counters, and were especially prevalent in unsupervised small groups.

One explanation for students slacking and stalling is teachers are doing most of the talking and directing, and not providing enough opportunities for students to think.

How can we build “thinking” maths classrooms and reduce the prevalence of non-thinking behaviours?

Here are two research-based ideas.

Form random groups

Often students are placed in groups to work through new skills or lessons. Sometimes these are arranged by the teacher or by the students themselves.

Students know why they have been placed in groups with certain individuals (even if this is not explicitly stated). Here they tend to “live down” to expectations.

If they are with their friends they also tend to distract each other.

Our studies found random groupings improved students’ willingness to collaborate, reduced social stress often caused by self-selecting groups, and increased enthusiasm for mathematics learning.

As one student told us:

“I’m starting to like maths now, and working with random people is better for me so I don’t get off track.”

Get kids to stand up

Classroom learning is often done at desks or sitting on the floor. This encourages passive behaviour and we know from physiology that standing is better than sitting. But we found groups of about three students standing together and working on a whiteboard can promote thinking behaviours. Just the physical act of standing can eliminate slacking, stalling, and faking behaviours. As one student said, “Standing helps me concentrate more because if I’m sitting down I’m just fiddling with stuff, but if I’m standing up, the only thing you can do is write and do maths. ”

The additional strategy of only allowing the student with the pen to record others’ thinking and not their own, has shown to be especially beneficial. As one teacher told us: “The people that don’t have the pen have to do the thinking […] so it’s a real group effort and they don’t have the ability to slack off as much.”

Simple changes can work

While our studies were conducted in maths classrooms, our strategies would be transferable to other discipline areas.

So, while parents and educators may feel concerned about Australia’s declining mathsresults, by introducing simple changes to the classroom, we can ensure students are not only learning and thinking deeply about mathematics, but hopefully, enjoying it, too.

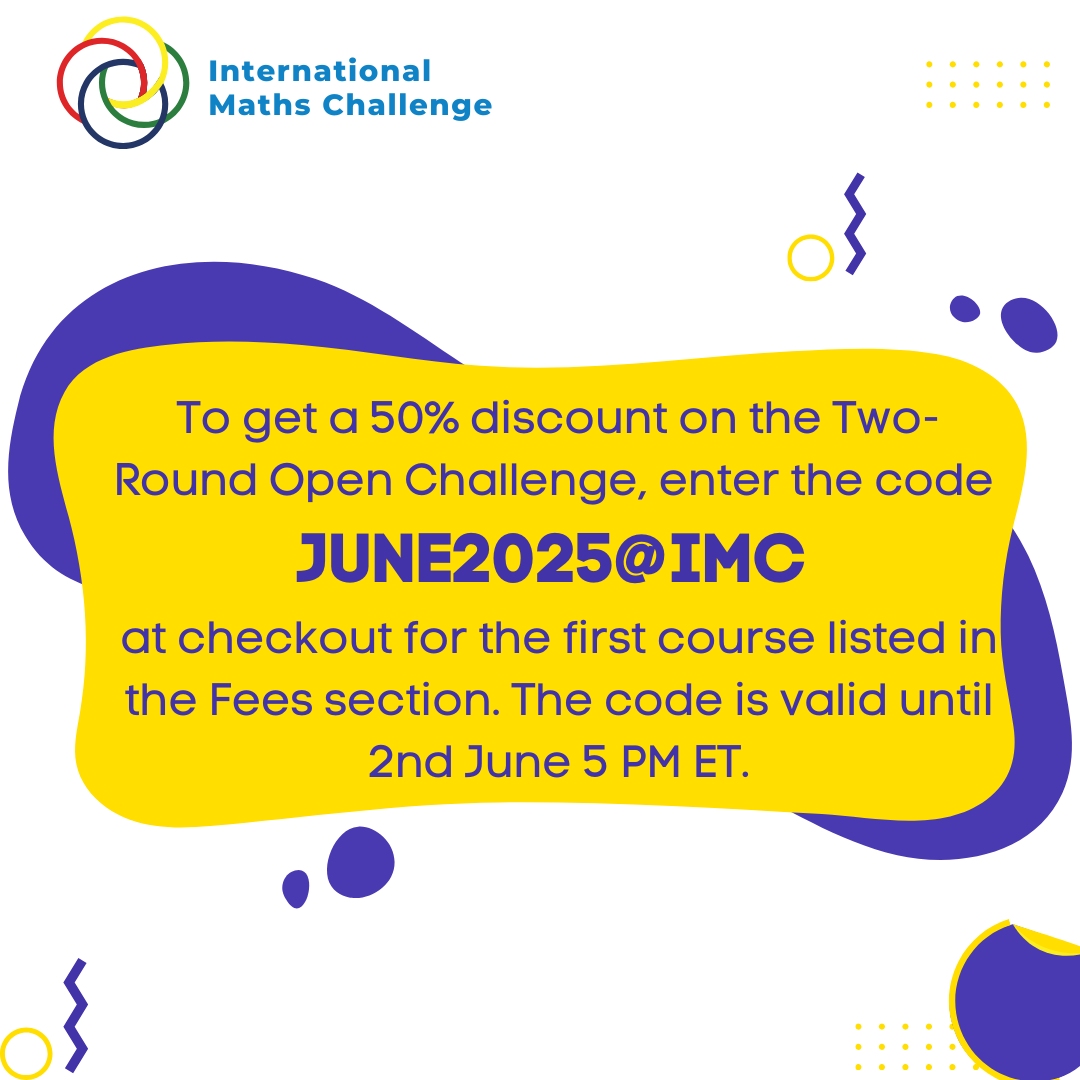

For more such insights, log into our website https://international-maths-challenge.com

Credit of the article given to Tracey Muir and Peter Liljedahl, The Conversation